Who are ‘the Caliva brothers,’ and why do they want to help felons sell legal weed?

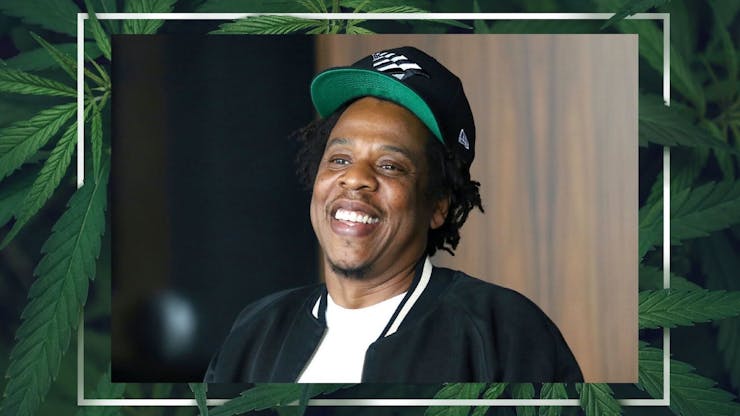

So far, so good, for Monogram, JAY-Z’s legal cannabis venture with Caliva. The rave reviews for the products are no surprise, given JAY’s successful Billboard and boardroom resumes. But the poetic justice of his path from illicit dealer to legal kingpin still reads stranger than fiction, even to him.

Almost three decades removed from wholesaling cocaine in New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia, the NYC native is still rapping about his odyssey from selling drugs to music. Now, nearly four years into a long-term partnership with Caliva, he’s moving weight again. And even he has to stop and ask himself from time to time: ‘This can’t be life, right?’

“All I know is E’s a felon, how is he selling weed?/The Caliva brothers, deep down, I believe you love us.”

JAY-Z, “Neck & Wrist” (2022)

On the new track “Neck & Wrist” with fellow Drug War survivor Pusha T, JAY sent a few kilos of clout to his new plug right before our ears. And he did it all while reminding the industry why legacy operators deserve respect, input, and ownership across the board–regardless of the qualifications or capital that less-rooted others may bring to the table.

Keep scrolling to learn why JAY-Z won’t stop rhyming about his highly unlikely third act in the legal cannabis market. And remember to @Leafly on social with your favorite songs, scenes, and moments that elevate the plant.

1. ‘E’s a felon, how is he selling (legal) weed?’

By now you may have heard that JAY-Z has a knack for cooking up dope rhymes about his life and times as a dope dealer. But his latest bars are about friend Emory Jones, who served most of his adult life behind bars during JAY’s rise to superstardom.

While most of America failed to empathize with the Drug War’s victims and survivors in real time, artists like JAY and others documented the carnage of the failed War on Drugs for the world to see. Encoding the country’s dark truths in rhyme, and sharing them with credibility that news outlets and education systems still struggle to uphold.

“They gave us drugs then turned around and investigated us,” JAY rapped in 1999, just three years after journalist Gary Webb tried to expose the US government’s role in importing cocaine through dealers like ‘Freeway’ Rick Ross.

Before weed was destigmatized, JAY-Z didn’t talk about it much on the record. He maintained a cold hustler’s mystique for the public. Peers like Cypress Hill, Snoop Dogg, and Redman carried the long tradition of artists using music to normalize weed. But most of JAY’s rhymes focused on the lifestyle that came with selling other prohibited plants.

While other MCs found ways to squeeze Mary Jane into almost any verse, JAY’s are jammed with warnings that he’s “from where the hammers rung, news cameras never come,” and “there was so much coke that you could run a slalom.”

As a child, he lost his father to opioid addiction long before America found empathy for that kind of thing. And his Brooklyn neighborhood was one of many ground zeroes for the Drug War that America waged on its own citizens. All of that should inform why JAY’s relationship with bud is more complex than the average cannaseur’s.

He says he lit up to overcome writer’s block while recording his essential hit, “Izzo,” in 2001. And that bud helped him cope with the lows of young adulthood when he was just trying to get by. But JAY mostly kept his distance from the dank until recent legal dealings. Even when studio sessions triggered childhood memories of his mother smoking weed to Curtis Mayfield records.

“This is my mama’s shit/I used to hear this through the walls in the hood when I was back on my pajama shit/Afros and marijuana sticks/Seeds in the ganja had it poppin’ like the sample that I’m rhymin’ with.”

JAY-Z, “The Joy,” (2011)

2. JAY-Z’s most notorious tree session

JAY wrote in his 2010 memoir Decoded that he once saw cannabis use as counter-productive. Back then, he limited consumption to vacations from high stakes work trips. On his 1996 debut, JAY admitted to indulging “once in a few, when (there’s) nothing to do.”

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries nearHis late great friend Biggie Smalls once peer pressured him to smoke at a 1996 video shoot in Miami. JAY remembers, “I could count the number of times I’d smoked trees (to that point).” But when B.I.G. asked him to smoke one at the beach, JAY had to remind himself that the first act of his life story was over: “Relax, you’re not on the streets anymore,” he thought.

They smoked before the video shoot. And JAY was so blazed, he had to take a 20 minute break in his hotel room. B.I.G. sensed JAY’s panic setting in, and leaned on his paranoia by whispering three words: “I got ya,” joked Biggie.

B.I.G. reportedly smoked 60 blunts while recording “Brooklyn’s Finest” with JAY earlier that year. But JAY was barely able to fight off a panic attack on set, swearing, “never again,” to his fellow Brooklynite as he tried to come down.

Oh, what a difference 25 years can make. Now, he can’t stop bragging about trafficking the (mostly) legal plant he once saw as a liability to his coke career. Almost every song JAY-Z’s released since the 2018 Caliva deal has infused at least a few milligrams of the dramatic irony he sees in going from bricks to Billboard records, then Grammys to legal Monograms.

“I’m sellin’ weed in the open, bringin’ folks home from the feds/I know that payback’s gon’ be mean, I’m savin’ all my little bread/Pray for me, y’all, one day I’ma have to pay for these thoughts.”

JAY-Z, “What It Feels Like” (2021)

Last year, JAY bragged about his Caliva connection on a posthumous collaboration with LA artist, activist, and Marathon OG strain founder Nipsey Hussle. JAY continues on the song, “IRS… trying to audit all my checks, too late. You know they hate when you become more than they expect.”

3. So who are ‘the Caliva brothers?’

When JAY drops the name “Caliva brothers” on his new song, it may sound like the nickname of an organized crime syndicate. But Caliva was actually founded by a Seattle woman named Shannon Harder Ronald in 2015.

In just seven years, the company has grown to be California’s largest single-state operator. BusinessWire says Caliva’s industry advantage comes from its “vertical integration and direct-to-consumer platform,” which allows for easy online ordering and same-day pick-up or delivery.

JAY recognized the company as the perfect vessel for giving OG’s their flowers. OGs including lifelong friends who didn’t get as lucky as he did. In a series of photos posted to Instagram, JAY poses joyfully with friends Lenny Santiago, Tyran “Ty-Ty” Smith, and Emory “Vegas” Jones. In the most recent flick, JAY sits beside Jones in front of the LA skyline with the caption, “The Caliva Brothers.”

JAY likes to leave some things to interpretation, so that may be the only hint we get about the brotherhood for a while. But it seems like the Caliva name could be a new family tie for old friends. Many crews adopt names from streets signs, famous outlaws, or designer brands, but own zero equity in the words they rep. ‘The Caliva Brothers’ seems like another example of JAY appropriating corporate resources for a greater good.

He helped his friend Emory come home 15 months early from a 16-year drug sentence by writing a letter to the judge and providing opportunities in the fashion industry. For the decade and change Emory was gone, JAY also kept his name alive in his music. “(I) lost my homie for a decade,” he said on 2012′ “Clique,” “Down for like twelve years, ain’t hug his son since the second grade.”

Court docs show that JAY’s letter to his friend’s judge helped trigger a Supreme Court decision on inequity in sentencing between crack cocaine and powdered cocaine. And a year before jumping into the legal weed business, JAY marveled at how quickly cannabis was destigmatized and normalized.

“You got ladies on The Today Show talking about weed makes them better parents… There are people in jail!”

JAY-Z, “Rap Radar Podcast” (2017)

Imagine if the entire industry took the same stand to never let America forget the 40,000-plus estimated prisoners of cannabis prohibition.

4. ‘I sold kilos of coke, I’m guessing I can sell’ some trees?

Today, lawmakers and weed companies are scrambling to address social equity and the contradictions that legalization presents. But JAY entered the conversation in 2018 with one of the few voices that can speak as both a victor and a victim of the Drug War.

“Any type of paraphernalia, I am the seller, I guess they’re saying that’s how we started Roc-A-Fella.”

JAY-Z, “Ain’t I” (2007)

“Sold drugs, got away, Scott free,” he teased on 2020’s “What’s Free,” confident the statute of limitations would protect him from retroactive punishment. “Feds all fed up, DEA can’t tell the dirty money from a Rocawear sweater, and I’m never, ever going back,” he taunted on an unreleased song from 2007.

After labels passed on signing him, the Roc-A-Fella Records label JAY co-founded with drug money let him side-step the music establishment. Backed by proceeds that JAY, and partners Damon Dash and Kareem “Biggs” Burke saved from the streets, ‘The Roc’ incorporated in 1995, claiming complete creative and executive control of their product.

They took creative risks, and did the groundwork to record, print, and market JAY’s music on their own terms. And when they finally struck Billboard gold on his third album (selling over 5 million records behind the hit single “Ghetto Anthem (Hard Knock Life),” the profit margins crushed the competition.

While most peers were stuck in bad deals that had them lucky to break even after selling millions, JAY, Dame, and Biggs became the poster boys for self-determination in a country that celebrates capitalism by any means. JAY was the star, Dame the CEO who took zero shit, and Biggs the silent muse who fed the rapper stories, slang, and style tips from personal episodes.

Biggs was eventually arrested in 2010 and sentenced to 5 years for moving kilos of green between Florida and New York.

5. ‘Cut from the cloth of the Kennedys’

Charmed by the myth that Joe Kennedy fathered America’s unofficial royal family by bootlegging liquor, JAY made his career the blueprint for the next generation’s highest self-made ambitions.

But be clear, the Roc’s brand was never about compromising to “make it” in America. Reasonable Doubt, JAY’s 1996 debut, was a manifesto for hostile takeovers that stole back the dreams America hoarded from select citizens.

Over time, the example set by Roc-A-Fella, and similar indie operations in Louisiana (No Limit Records, Cash Money Records), Texas (Rap-A-Lot Records), and California (Sick Wid’ It Records and Up All Nite Records) taught rappers to approach major record companies as business partners instead of starving artists.

The new standard was finding distribution and owning your music, not trading ownership for a lump sum of advance money. But the startup capital had to come from somewhere.

6. ‘Pay us like you owe us’

Right now, lawmakers in JAY’s former stomping grounds of New York and New Jersey are looking for ways to keep big money from cannibalizing the cannabis industry’s growth in the same ways JAY and company sought to protect the integrity of their music. Whenever federal prohibition ends, a flood of corporate budgets will hit the cannabis industry. Many of the lessons cannabis legacy entrepreneurs will need to navigate post-prohibition can be found in JAY’s second act as a rap star.

Less than 20 years after JAY’s debut, rap music grew from a maligned ‘trend’ to the most popular genre of music in the world. And drug dealers like him went from super predators to super heroes. Both changes were due in part to JAY’s influence.

In 1998, a federal act known as the DMCA was passed. It expanded the ways corporations could exploit rap music’s shock value on the global market. And JAY thrived in the grey area between the law and the court of public opinion, taking pride in the ability to exploit himself on his own terms while other artists were weighed down by the moral dilemma of “selling out.”

Labels saw how valuable urban America’s war stories were on the open market, and real dealers nationwide began to see music as a miraculous path to legitimacy. Over time, stacks of cash and illicit ties became barriers that protected Hip Hop from circling vultures in suits.

Like legacy operators in the cannabis industry, JAY and his partners bet against the casino long before laws or streaming data could validate their dreams. But going against the grain required them to sell their content with the same ruthlessness that got them through the Drug War.

The industry that sprouted around rap music became raw terrain to carve new American dreams. JAY aimed to leave the boldest mark; Boycotting the Grammys, and billing himself as “The ghetto’s answer to Trump,” and “cancer to the Hamptons.” (He now owns a vacation home there).

He delivered solo albums in eight straight years (1996-2003), bragging that he could “match a triple platinum artist buck by buck” while selling a fraction as many records. “I’m overcharging (labels) for what they did to the Cold Crush (Brothers),” he rapped on “Izzo,” name-checking some of Hip Hop’s unsung pioneers. But symbolic victories only went so far. The mission he is pursuing requires lifetime dues.

7. ‘That marketing plan was me’

With the Parent Company umbrella covering a ‘house of brands’ that includes Monogram and Caliva, the blueprint for JAY’s latest corporate takeover is getting the green light from reviewers and industry analysts. The stock price and earnings have been up and down, but the company’s leadership has expressed confidence in future growth. JAY’s proven track record of trafficking influence may have something to do with that.

When the Rocawear fashion line sold for $204 million in March, 2007, JAY secured the war chest and proof-of-concept needed to challenge the music industry’s status quo. And for the next decade he built an eco-system of brands that turned his intangible influence into a commodity.

Music, like cannabis, is not an easy product to industrialize. Science shows that music triggers the same reward systems in our brains as cocaine and alcohol. But packaging and scaling that experience is more art than science.

JAY’s Caliva shoutout will scale the brand’s name on search engine algorithms and the minds of listeners for generations to come, a move he used to give away for free to companies like Cristal before creating his own high-end Ace Of Spades Champagne. He learned long ago that no amount of marketing dollars can plant that kind of influence overnight.

He patented these moves by stacking endorsement deals with Reebok (2003) and Budweiser (2006) and turned the momentum into artist-empowerment tools like Roc Nation and Tidal. He used those and his own experience to help shepherd artists like Rihanna, J. Cole, and Beyoncé past corporate sharks that freely preyed on stars before the influencer era.

Today’s influencer economy runs on many principles that JAY helped pioneer decades ago. Rapper-turned-cannabis moguls like Wiz Khalifa (Khalifa Kush), Berner (Cookies), and Young LB (Runtz) have borrowed whole chapters of JAY’s marketing playbook to build international cannabis brands ahead of federal legalization.

And JAY’s weed moves aren’t just boosted by lighter laws and his rich network. The self-awareness he’s gained from wins and losses in Marcy Projects, music, and corporate meetings will help show the cannabis industry how to balance the needs of both the corner and the corner office.

“Well, we hustle out of a sense of hopelessness/Sort of a desperation/Through that desperation, we become addicted.”

JAY-Z, “Can I Live” (1996)

8. ‘Che Guevara with bling on’

JAY once called himself “Che Guevara with bling on,” but also said “I can’t do numbers like The Roots,” Common, or Talib Kweli because socially conscious lyrics don’t sell. Lately, he been more open about his unusual political evolution from studying kingpins like Pablo Escobar to revolutionaries like JoAnne Chesimard (Assata Shakur).

in 2021, JAY’s much-scrutinized deal with the NFL got some ‘sell-out’ jeers, while others celebrated the historically dope halftime show his Roc Nation company produced for the big game.

And while the shrewd deals he’s arranged with Samsung (2013) and Sprint (2017) boosted his streams and proved he could sell “water to a whale,” it’s gotten harder to pretend those personal wins trickled down to the people as much as he once claimed.

In 2011, the family of Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton rebuked a lyric that pointed out JAY was born the same day Hampton was assassinated by Chicago police and the FBI. But they eventually made peace, and JAY donated the proceeds from a 2021 song to the estates of Hampton and Nipsey Hussle.

He was also mocked for claiming ownership of the NBA’s Brooklyn Nets, before it was revealed that he “owned” less than one percent of the team. JAY addressed those claims once on stage. But the rapid development of the Nets’ new Barclays Center arena in his hometown also brought flack in national discourse about gentrification.

After decades of fielding valid criticism, it’s hard to knock JAY’s new ventures as anything less than visionary. He’s no longer hustling out of a sense of hopelessness, or trying to walk the thin line between Robin Hood’s generosity and Donald Trump’s hubris. His third act in legal weed is a dream retirement gig for any American, let alone one that was once projected to be dead or in jail before 25.

“Back when Emory Jones was facing a fed charge. I knew less about Chesimard, all about Pablo Escobar/Thinking I was the last one Allah would lay his blessings on/I was just trying not to end up like Tony in the restaurant.”

JAY-Z, “Universal Soldier” (2020)

9. ‘Drug dealers anonymous’

Before the cannabis industry had terms like ‘legacy operator’ to nod to ‘the old way of doing things,’ Hip Hop put local dealers first. The market forces outlined above made the rap industry a survivor’s group for veterans of the Drug War. And not just because drug money was helping pay the bills.

JAY, B.I.G., Nas, and Scarface helped coin a genre of ‘coke rap’ that continues to drive traffic to this day. For descendants like Pusha T, Young Jeezy, and Benny the Butcher, a collaboration with JAY is like an A1 stamp on a brick of product. Mr. Carter’s verses are validation for survivors of the hustle, from a Hall of Famer who knows the game is deeper than rap.

“My tenure took me through Virginia,” JAY reminds listeners 2015’s “Drug Dealers Anonymous,” alongside Pusha T. He tells skeptics: “Ask the Federalis ‘bout me/Tried to build a cell around me/Snatched my ni**a Emory up/Tried to get him to tell about me/He told 12, “Gimme 12”/He told them to go to hell about me.”

America began criminalizing drugs way before Hillary Clinton dubbed young men like JAY and Emory super predators, in a speech supporting her husband’s 1994 Crime Bill. President Joe Biden sponsored that bill, which criminalized millions of Americans overnight. The President is still yet to deliver on campaign promises to free and forgive all cannabis offenders. But in 2019 he stated: “Nobody should be in jail for smoking marijuana.”

While most modern politicians will claim their intentions with the Crime Bill were not malicious, the pioneers of agencies like the DEA, and policies like the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, and the Controlled Substance Act, were very clear about what the War on Drugs was truly about.

In the early 1900s, marijuana was used to justify violence and discrimination against Mexicans by border patrol agencies. Then in 1968, the Nixon White House identified two groups as domestic enemies: the antiwar left (hippies), and Black Americans. The administration decided to use drugs to declare an uncivil war.

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war, or Black. But by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin… And then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders. Raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

John Ehrlichman, former Nixon domestic policy chief (2016), Harper’s Magazine

10. ‘Lucky me’

JAY-Z narrowly avoided a drug raid while visiting London to record music in 1989. He knows things would be different if he hadn’t chased his music dreams over the pond.

“Up until that (London trip), my life could be mapped with a triangle: Brooklyn, Washington Heights, Trenton,” JAY wrote in Decoded. He was joined on the life-altering trip by Irv “Gotti” Lorenzo, a boisterous producer and executive who would go on to assist some of JAY’s biggest wins.

Another close call came in 2005, when Irv’s Murder Inc. record label defeated a federal case that tried to tie their music profits to drug money. JAY showed his support in court the day Gotti and his brother were found not guilty. If Murder Inc. had lost that case, the precedent could have derailed every move JAY’s made since.

You might want to call him a lucky bastard. But he’s closer to destiny’s child. After near brushes with bullets and the boys in blue, JAY’s been blessed to reach his AARP years with almost two B’s to his name, a Queen Bey in his corner, and a growing kingdom to share it all with. It might seem far-fetched if we hadn’t seen it all happen in real time.

“Live every word that I’m rapping,” he told listeners on 2018’s “Talk Up.” “You probably wouldn’t believe everything that you’re seeing right now if it wasn’t live action.”

From the uncle who told him he’d never sell a million records, to the record labels that showed him they felt the same, JAY uses doubters like a muse, addressing their slights on his next song. You know, where every spin turns him a profit.

Even comedian Faizon Love, whose speculation that JAY was “never a drug lord, but a puppet” triggered this new verse, has to nod to the ice cold counter that opens “Neck & Wrist:” “The phase I’m on, love, I wouldn’t believe it either/I’d be like, ‘JAY-Z’s a cheater,’ I wouldn’t listen to reason either,” he jabbed back.

Get it? “The phase-I’m-o”–never mind. And this guy claims he doesn’t smoke a lot of weed.