The world first learned about Biotech Institute LLC two years ago in an explosive GQ featureby Amanda Chicago Lewis called “The Great Pot Monopoly Mystery.” In the story’s opening scene, Lewis describes getting approached at a cannabis industry event by “a faun-like 40-something man named after a character from The Jungle Book.”

Biotech Institute 'could sue people for growing in their own backyards,' warned one competitor.

That was, of course, Phylos Bioscience founder Mowgli Holmes, whose own controversial business practices were profiled in part one of this series.

Holmes warned Lewis that a mysterious company had begun registering patents on cannabis “so strict that almost everyone who comes in contact with the plant could be hit with a licensing fee: growers and shops, of course, but also anyone looking to breed new varieties or conduct research.”

Biotech Institute’s patents, Holmes warned, could conceivably give the company global control over cannabis: “They could sue people for growing in their own backyards,” he warned. “And the craziest part is no one knows who’s behind this or when they plan to enforce what they have.”

Patenting cannabis: a special Leafly series

Who runs Biotech Institute?

According to its website, Biotech Institute LLC “develops groundbreaking, novel, and sustainable therapeutic products by optimizing the naturally occurring resources found within all living organisms.”

But what does that mean, exactly? And who stands behind Biotech Institute? The short answer is nobody really knows. And they didn’t reply to my emails—at least not at first.

The website’s “Who We Are” page doesn’t name any officers or employees of the company, or divulge any ownership information. But it does list an address in an office park outside Thousand Oaks, California.

So I paid them a visit.

Hello, anybody home?

Around 11 a.m. on a Tuesday in September, I arrived at an aggressively nondescript office park. Aside from a strip mall of upscale eateries a short walk down the road, there’s really nothing nearby but indistinct places like this one, where companies you’ve never heard of do things they mostly don’t want you to notice.

The company lists no names on its website, but claims to be based in Thousand Oaks. So I paid a visit.

In an afterthought of a courtyard, half a dozen carp swam in tight circles in a tiny pond, endlessly seeking a nonexistent path to open water. Otherwise all was eerily still as I approached Suite 226. A woman answered my knock and initially looked perplexed—then a bit annoyed when I explained that I’m a journalist. It’s a small office, one that clearly does not get a lot of visitors.

From the back emerged a white-haired man with a tight-lipped smile and crisp blue jeans. He stepped away from a floor covered in three ring binders to introduce himself as Carl D. Hasting—attorney at law and certified public accountant.

I said I’d come looking for Biotech Institute LLC. “This is the address listed.”

“I’m the lawyer for the company,” Hasting told me. “I couldn’t answer your questions if I wanted to.”

Okay. Who can answer my questions, I asked.

“I couldn’t begin to answer that.”

‘Get in touch with Gary Hiller’

Hasting explained that he functions as outside counsel for Biotech Institute. Eventually he suggested I contact Gary Hiller.

Hiller is the president and chief operating officer of Phytecs, a Los Angeles-based cannabis biotech startup associated with former California congressman Tony Coelho. A lawyer, former Congressional aide, and self-described “seasoned business executive,” Hiller has played a key but unquantified role in the rise of Biotech Institute and a cluster of other companies in the cannabis biotech space.

“Gary Hiller works for [Biotech Institute],” Hasting explained, “while [Biotech Institute] is a client of mine.”

I reached out to Gary Hiller.Eventually, he responded to me via email, but declined to disclose the names of any employees, executives, or investors in the company.

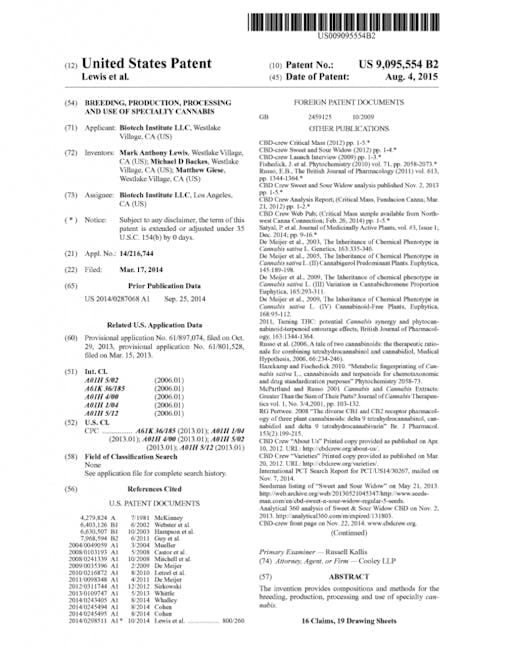

Patent #9095554B2

The sizzle copy on Biotech Institute’s website alludes to developing “proprietary approaches” to mitigating harmful impacts of THC, developing advanced medicinal applications for cannabis, and helping growers “enhance their yields through non-chemical means, while simultaneously reducing the risk of harmful pests and disease.”

But it never directly mentions that Biotech Institute has been steadily seeking out patents on the “breeding, production, processing, and use of specialty cannabis.” In 2015, the company was granted US Patent 9095554B2, the first ever directly related to cannabis genomics. It’s a doozy.

Patent 9095554, issued in 2015 to Biotech Institute LLC.

A powerful ‘utility patent’

While plant patents cover one distinct strain, utility patents like #9095554B2 are far more expansive and cover wide ranges of plant characteristics. It’s the utility patents that most concern those worried about a Big Ag takeover of commercial cannabis cultivation.

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries nearMowgli Holmes has claimed that Biotech Institute’s existing patents could give them leverage over “almost anybody who comes in contact with the plant.” But given Holmes’ spotty track record for transparency, I thought it best to seek out a few additional expert opinions.

A patent on all THC:CBD plants?

Kevin McKernan was a research and development manager on the Human Genome Project (HGP), and one of the first scientists to sequence the cannabis genome. He now serves as Chief Science Officer at Medicinal Genomics, a cannabis science company we’ll learn much more about in part three of this series

I asked McKernan about the scope and power of Patent #9095554B2. “In the broadest reading of it,” he told me, “you could say they have a patent over all Type 2 cannabis plants that don’t have myrcene as the dominant terpene.”

Since Type 2 basically refers to cannabis plants that produce significant amounts of both THC and CBD, that’s an extremely broad patent, in the hands of a decidedly shadowy operation. Though McKernan is not so alarmist as Mowgli Holmes.

“I do not doubt that the talented team at Biotech Institute bred something novel and unique, and they have excellent documentation to back up what they have done,” McKernan said. “But I think the gap lies with how broad the claims stand. Still, it’s anyone’s guess how this will play out, as the cannabis industry is new to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.”

The patents might not be valid

I also asked Dale Hunt, who is both a registered patent attorney and a lawyer specializing in cannabis, to weigh in.

Hunt told me that Biotech Institute’s “most expansive patents are widely believed to be invalid,” adding, “That’s not a legal opinion but rather a restatement and summary of numerous conversations I’ve had with people in the industry who attest that the chemotypes claimed in these patents are simply not new. If that is indeed the case, then the patents would not be valid.”

Tracking down the inventors

In addition to Patent #9095554B2, Biotech Institute also holds cannabis patents covering methods of analysis and classification systems; utility patents covering plants with novel chemistries; plant patents covering particular cultivars; cannabis propagation methods; and composition claims.

This includes six separate utility patents (like #9095554B2) that cover broad ranges of plant characteristics. And in just the past year they’ve applied for additional patents tied to specific cannabis strains, including Lemon Crush, Cake Batter, Primo Cherry, Holy Crunch, Rainbow Gummeez, Guava Jam, Grape Lollipop, and Raspberry Punch.

My first attempt to shed light on the company’s backers ended up at the dead end of a Thousand Oaks office park. But there were other clues to follow. Every patent is registered to both an assignee (who owns the patent) and an inventor. All of which is public information.

So I sought out Michael D. Backes, Mark Anthony Lewis, and Matthew W. Giese—the three men listed as inventors on Patent #9095554B2.

Biotech’s dream team

Individually and together, the three inventors listed on Biotech Institute’s first patent have made huge contributions to the world of cannabis science. They have a legacy of research and innovation that they’re justifiably proud of, and one that has provided significant benefits to cannabis breeders, growers, consumers, and patients around the world.

But when it comes to talking about patents, they turn evasive.

Matthew Geiss declined to speak with me at all.

Mark Lewis graciously spent two hours with me on the phone, without ever disclosing how exactly Biotech Institute LLC gained control over his inventions, or what he got in return.

Michael Backes at first flatly refused to discuss patents, then fired off a series of increasingly contentious and insulting emails in response to my questions. Ironically, those emails came closest to answering my questions. But more on Backes in a bit.

First, let’s start with Mark Lewis, an idealistic cannabis enthusiast with a PhD in biochemistry from Purdue.

Mark Lewis: garage inventor

Almost immediately after earning his PhD in 2007, Lewis moved to California to pursue “innovation-focused work” in the cannabis space. Initially he set up a lab in his own garage, he said, “like the start of Silicon Valley.” Then in 2011, Gary Hiller came along and helped him incubate a “data-driven plant science” business called Napro Research, where he remains president to this day.

Yes, the same Gary Hiller who works for Biotech Institute.

Lewis says that when Napro started, the laboratories testing cannabis didn’t have validated methods. So he “hired three chemists from Pharma and started writing validated methodologies” that were then published open source, so any laboratory in the world could use them, all in an effort to elevate testing standards to benefit both the industry and consumers.

I asked when his focus shifted to creating patentable intellectual property, and how Biotech Institute ended up as the beneficiary of that research.

Lewis responded by defending the importance of patents, biotech, and Big Ag.

“I’m not a patent lawyer,” he told me. “I’m a researcher. My contribution is innovation, not patents. I’m motivated by expansive outside-of-the-box innovation. The IP merely helps justify the time, energy, and resources spent during the innovation process.”

Above: Mark Lewis, speaking at DefCon 26 in Las Vegas in August, 2018.

“Did Biotech Institute fund your work?” I asked.

“They supported our work, yes,” said Lewis.

“Did you have an understanding of how they planned to use those patents to secure a return on that investment?”

“No,” he said.

And what if Biotech Institute planned to follow the Monsanto model?

“I definitely don’t have a crystal ball,” Lewis said, “but I do like to point out that there’s a lot more food available to a lot more people in regions where malnutrition and starvation were commonplace because of companies like Bayer/Monsanto and their innovations.”

Lewis also confirmed that Biotech Institute has already begun working with cannabis and hemp farmers—“over a dozen in six states,” he said. Those farmers contact Lewis’ company, Napro, for access to proprietary genetics. The farmers then pay Biotech Institute a licensing fee.

The latest breeding technologies

As one example, Lewis points to Molecular Farms, “an all-organic grower of premium cannabis, using the latest breeding technologies” that in 2017 won Best CBD Flower (Guava Jam) and Best Overall Flower (Lemon Crush) at the prestigious Emerald Cup.

Both strains are patent pending, with Mark Lewis as co-inventor and Biotech Institute as assignee. Lewis says Napro and Biotech Institute have also been supplying patented CBD-rich hemp cultivars to commercial farmers, including many eager to find a profitable, eco-friendly crop to replace tobacco.

I finished our long conversation with a greater appreciation of how much Lewis and his fellow inventors have contributed to our understanding of the cannabis plant, and how their breeding of new next-generation strains can produce marked improvements in everything from plant yield and drought resistance, to tailored medicinal effects and wholly unique terpene profiles.

But what’s frustrating is that he refuses to acknowledge that there’s a considerable trade-off involved. That biotech companies acquire utility patents on plants not to help humanity, but to increase profits, consolidate power, and—eventually—vertically integrate their operations. Until they’ve sucked up as much market share as possible while leaving their competitors (and the Earth’s topsoil) in the dust.

That’s how Big Ag have grown ever bigger, richer, and more politically influential over the last fifty years, while during the same timespan, America’s small family farms have been disappearing in droves. So maybe those of us worried about the same thing happening to cannabis aren’t so naive as we look.

Michael Backes, author of Cannabis Pharmacy, is well known and respected in the cannabis world. But he gets testy when asked about his work for Biotech Institute. (Gillian Levine for Leafly)

Michael Backes himself into a corner

In 2007, Michael Backes founded the Cornerstone Research Collective, a pioneering patient-focused California medical cannabis organization. Backes was a founding board member of the National Cannabis Industry Association, his book Cannabis Pharmacy: The Practical Guide to Medical Marijuana is one of the foundational works in the field, and he’s a frequent guest lecturer at universities around the nation.

'I don't do interviews about patents,' Backes told me. 'I write them.'

He initially told me via email that he won’t offer any comment on cannabis patents, including those that list him as co-inventor.

“I don’t do interviews about patents.I write them.Nothing comes from speaking about them… And to clarify: I do not get money in any form from my first utility patents. Never have received money or royalties or license fees or stock. Never will… I do not own any financial interest in ANY patent grant, directly or indirectly.”

Which sure sounded odd, not just because he would have performed an awful lot of painstaking work without “any financial interest,” but also because those patents didn’t enter the public domain, they became the property of Biotech Institute LLC, a privately held company with almost no public face. Something didn’t add up.

“What motivated you to pursue and put your name on those patents,” I asked, “if it was not a financial incentive?”

Here’s a taste of the email exchange that followed:

Backes:Because when I started in 2011/2012, nobody had ANY Type II cultivars that weren’t loaded with myrcene. ALL CBD cannabis tasted like a rope cured in shit… This is when California’s idea of a state-of-the-art cannabis lab was run, respectively, by a degenerate poker player and a warm, friendly stoner. Back when I tried to explain terpene pharmacology to you [in a 2012 High Times interview], you looked at me like my Border Collie looks at me when I speak Spanish. I had a state-of-the-art chemistry lab solely established for exploring the plant and not just trying to cultivate crap that breaks 30 percent THCA. Run by two real ex-pharma chemists with decades of cannabis cultivation experience. We did it simply because we were the only folks in the US that could.

Leafly: Okay, admittedly I’m a little slow, so let me make sure I’ve got this right. Because you’re so much smarter than everyone else you pursued these patents with no financial gain for yourself (direct or indirect) and thereby effectively put these valuable patents in the hands of…. who? And what made [Biotech Institute LLC] worthy of such a selfless gift?

Backes: No I am DEFINITELY not smarter. Just got VERY lucky and started much earlier on the science/raise money to do science front… What made them worthy??? LMFAO! Oh, please, selfless one. The person who wrote my check, your check, anybody’s check. Don’t want to keep you, your work at the soup kitchen is waiting...

I do not benefit from the patent and my sole intent in writing it was to create organoleptically pleasing Type II cultivars and homozygous seed to sell.

Leafly: I’m not disputing that your ‘sole intent in writing it was to create organoleptically pleasing Type II cultivars and homozygous seed to sell,’ but that leaves open the question of your intent in granting Biotech Institute the role of assignee.

Backes: When I have an idea for a patent and write one, whether I work for the Red Cross, the CIA, Harvard, or Monsanto, they own it. I have to assign it, but so does every single limp dick that creates IP for a company anywhere in the known fucking universe.

Don’t hate the player, Michael Backes seemed to be telling me. Hate the game.

Fund researchers, reap patents

Not long after my back-and-forth with Michael Backes, I received an emailed reply from Biotech Institute offering to let me submit questions in writing.

I asked about their patents—how expansive are they? And has Biotech Institute LLC ever had cause to enforce them?

To which Gary Hiller, Managing Member of Biotech Institute LLC replied:

“Although BI’s aggregated patent portfolio is expansive, each individual set of allowed patent claims is narrowly tailored to cover a particular, specified invention… Today, BI is focused exclusively on facilitating continued innovation to benefit farmers, adult-use customers, medical patients, and public safety generally. We will address the issue of enforcement if and when it is prudent to do so.”

Is it possible that Biotech Institute LLC would ever sell one or all of its patents to a company like Monsanto/Bayer?

“We license our technology and provide support in the form of genetics and other know-how to assist our partners to produce award-winning cannabis. It is possible that some could view these partners as falling within the category of companies cited in your question. Separately… the phrase ‘a company like Monsanto/Bayer’ seems to reflect an inherent bias that we do not share.”

Girding for a patent war

So far Biotech Institute has licensed its patented seeds and clones through partners like Mark Lewis’ company Napro, but has not yet enforced its cannabis patents. Perhaps they never will. But with so little known about the company, it’s also not hard to imagine them patent-trolling the entire cannabis industry.

All they would have to do to ignite the Great Cannabis Patent War is send a single letter to a commercial cultivation operation claiming infringement and demanding retribution. Thus leaving the grower with a choice: pay up, or fight it out in court.

Even if you mount a successful defense, legal fees alone can easily reach hundreds of thousands of dollars or more. For a small operation, that’s often too bitter a pill to swallow, especially when you could conceivably spend all that money and still lose.

Right or wrong, for most companies hit with a patent claim, it’s often wiser to just give them what they want. Which is exactly how Big Ag got so big in the first place.

Coming in Part 3: A leading genetic scientist wants to open-source the cannabis space. What’s behind his crusade to move cannabis DNA into the public domain?