When Oakland’s Fantastic Negrito won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Blues Album in 2017, for his debut LP The Last Days of Oakland, he didn’t celebrate at a private party, surrounded by the Los Angeles music industry. No, he took his Grammy down to the local train station and busked, as he has done for years.

It was perhaps the perfect summation of Fantastic Negrito – born Xavier Dphrepaulezz – who, even after he won NPR’s inaugural Tiny Desk Competition in 2015, catapulting him to national fame, has remained devoted to the city he knows so well. Fantastic Negrito’s songs have long addressed the challenges facing the San Francisco Bay Area — from the pitfalls of gentrification to the value of diversity. Yet for all of his love for the Bay Area, it’s not often that he shares stories from his past as a pot dealer there. We caught up with Fantastic Negrito on the release day for his dazzling sophomore album, Please Don’t Be Dead (out 6/15), to reflect on his storied history selling cannabis in Oakland, the themes behind his new music and where the two intersect.

Be sure to catch Fantastic Negrito on a world tour this summer, taking him and his band from Nashville to the Netherlands. Because even if you aren’t from Oakland, the universal truths radiating through PleaseDon’t Be Dead – from the self-empowerment anthem “Plastic Hamburgers” to the righteous anger of “The Duffler” – will still strike a chord.

You’ve lived in Oakland for much of your life – what are some of your earliest memories of cannabis there?

It was like drinking water when I was a kid growing up in the ‘80s. It was such a part of the culture, such a part of the neighborhood. We never thought twice about it. I’m so old I remember smoking Colombian Gold (laughs).

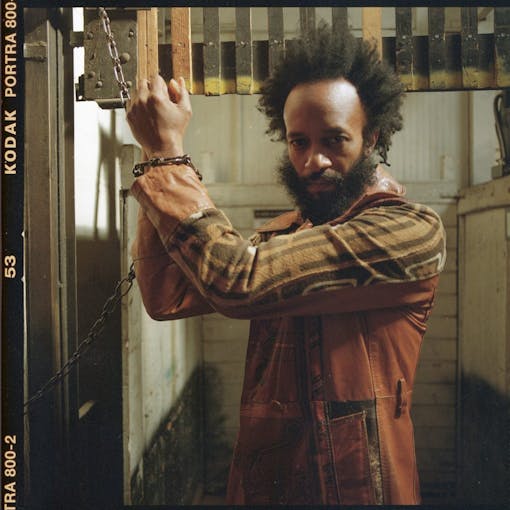

Fantastic Negrito (DeAndre Forks, Courtesy of Big Hassle Publicity)

It was economic, that’s what I loved about it. My auntie, who was living in West Berkeley on 9th Street, she had nine kids but she was selling herb. She wasn’t happy to take food stamps or handouts from the government, and she was empowering herself economically, taking care of all those kids through cannabis sales.

I ran away from home at twelve, and the first thing I did [in the Bay Area] was cop it from my auntie. She was the cool person in the family; I lived [near her] in my cousin’s car. She would front me ounces and I would turn ‘em over, and smoked the hell out of it, too.

Living in poverty, we could all get together [and smoke]. It was very festive; it always felt tribal. For some of my friends who own houses on [Oakland’s Lake Merritt] now — black men who didn’t finish high school — it was a way out of poverty.

We had sick, older people in the community. We’d say to them, ‘Hey, stop taking your prescriptions, try cannabis.’ We’d donate some to the older ladies; they would take the stems and boil them and make tea to treat multiple sclerosis, someone recovering from cancer. That’s one of my proudest moments, that I could do something for those people. That’s community.

Is there a longtime connection between cannabis and music for you?

Of course (laughs). Cannabis was looked at as so joyous and exciting. You had a date with your little teenage girlfriend, you’d roll it up and you’d kick it. Of course Dr. Dre blew it up with The Chronic, but I remember Cheech and Chong, Up in Smoke. We were real little but we were into that movie. We got all the jokes.

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries nearThat’s how we got all our [musical] equipment, grindin’ away. That’s how everything happened, even up to Fantastic Negrito. I was in the [Blackball Universe Collective], and one guy [Malcolm Spellman] was a writer, but he was broke. We said, ‘Hey, let’s help him so that he can write and pursue his dreams.’ He went on to be a writer at Empire. No cannabis, no Empire. That’s real.

No cannabis, no 'Empire'. That’s real.

Artists, instead of begging the gatekeepers, the motherf*ckers with their sick, repressed fantasies about how they think you should be and I should be, and what box you can fit in, we’re gonna use the power of the herb and empower ourselves. I learned everything from growing weed. That’s how you learn about people. That plant is magical.

Plants are like people: people have potential. Instead of having jails for these kids, how about we provide for them, give them life, check their pH (laughs). Guess what? We’re gonna have a beautiful society. We won’t have this crap we’re living in now, and I won’t have to write an album like The Last Days of Oakland. If we nourish these people and pay attention to their needs, they’re gonna provide for their community and their country.

What you’re saying reminds me of a message I hear throughout Please Don’t Be Dead – loving yourself and sticking together when things get rough.

Fantastic Negrito’s ‘Please Don’t Be Dead’ comes out this summer.

We’re living in an era where we gotta listen to Trevor Noah and Dave Chappelle; artists are carrying the real narrative. Leaders on both sides, they’re done. They’re extremists, they’re bought and paid for. What’s on my mind, in that tradition of artistry, is to also get out there on the front line and be an advocate and a voice of the people that help put me here, the community I started in the Bay Area walking down the street [and playing music].

The people in power are takers, people on the ground are givers and we gotta help the people they’re fooling. Please Don’t Be Dead is about celebrating yourself, smashing the ivory tower, smashing the gatekeepers’ ideas that you fit into their red state and blue state. We fit in the love state.

How does it make you feel watching the industry change in Oakland?

Don’t let big business come and snatch cannabis away, because it’s a plant of the people. A plant of the community. I don’t want people to lose control and power of cannabis; it’s very American in my opinion. It’s the one industry where you can get in there with a small pittance and make incredible things happen.

Lastly, I’d be remiss to not ask: are you still a consumer?

I’m not right now. I’m an advocate, I respect it. If I need it, it’s gonna be there (laughs). To me it’s a culture, it’s a resource, it’s a teacher.

Max Savage Levenson is a New York-based freelance journalist. His work has appeared in Pitchfork and NPR.