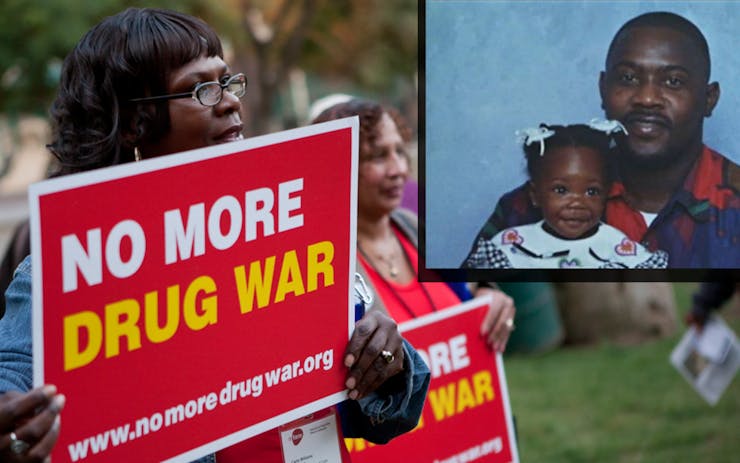

Bernard Noble, one of America’s most famous drug war victims, will be a free man by the end of this week.

On Tuesday a Louisiana parole board granted the 54-year-old truck driver his liberty. Noble served seven years and four months of a 13-year sentence for the crime of cannabis possession.

“We’ve had people receive sentences of life without parole for marijuana. Twenty-five years in prison? In Louisiana that’s a deal!”

In October 2010, two New Orleans cops found him holding two joints—less than three grams of cannabis. They arrested him. For that crime, and that crime only, Noble was sentenced to 13 years at hard labor.

Over the years that followed, Noble became one of America’s most famous drug war prisoners, a man who served as a living embodiment of the nation’s most cruel and nonsensical marijuana laws.

Bernard Noble will finally walk free. It gives me great pleasure to write those words.

Louisiana’s Cannabis Laws Are Medieval

Back in the spring of 2014, when I was researching my book Weed the People, I wanted to go to where America’s cannabis laws were the worst. If Colorado and Washington represented the leading edge of legal reform, what state harbored the trailing tail? I assumed I’d end up in Mississippi or Texas. I was mistaken. Louisiana’s cannabis laws were so extreme they bordered on the bizarre.

“We’ve had people receive sentences of life without parole for marijuana,” the longtime New Orleans defense attorney Gary Wainwright told me. “Twenty-five years in prison? In Louisiana that’s a deal!”

Noble’s case was just one of many. But his circumstances caught my eye. On that October afternoon in 2010, Noble wasn’t smoking in public. He wasn’t causing a disturbance. He was pulled over by two cops because he was riding a bicycle, legally. Noble was literally pulled over for bicycling while black.

In court, the truck driver and father of seven children was represented by a member of the New Orleans Public Defender’s office, an agency so notoriously overworked and underfunded that two years ago the entire office went on strike.

Prisons Don’t Fill Themselves

The case did not go well. Because Noble had two prior nonviolent offenses, committed decades earlier, state law required the judge to sentence Noble to a mandatory minimum 13 years in prison.

Leo Cannizzaro, the Orleans Parish district attorney, saw no reason to offer leniency. Cannizzaro is in the business of filling up the prisons of Louisiana, a state with the highest incarceration rate in the world.

Noble appealed his case, to no avail. The appellate court judge all but screamed in frustration. His hands were tied by state law. “This Court believes with all of its heart and all of its soul that this is injustice,” he said, before affirming Noble’s 13-year sentence.

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries near‘They Just Laugh’

“Bruce, I do not know why I’m in here. There are rapists and murderers walking around here. I gotta get out of here, man.”

That was Bernard Noble, talking to me via a prison pay phone, in 2014. He was trapped in one of Louisiana’s dozens of parish prisons, which make money by warehousing state “offenders,” as prisoners are officially designated. Offenders: At the time, Louisiana held more than 18,000 of them. In some rural districts, the local sheriff runs the state prison and as a result is the largest employer in the parish.

One time I reached Noble by phone—not an easy thing to do, believe me—at the Concordia Parish Correctional Facility, a parish prison out in Ferriday. “People ask me what I’m in for and I’m afraid to tell them marijuana,” he said. “Because they just laugh.”

I asked how he spent his days.

“I try to keep away from the crazy ones, the guys in here with aggravated charges,” he said. “I’m in this room with 45 other people. Every once in a blue moon they’ll let us go outside. But it’s so small a yard that we just end up staring at one another.”

The Price of Two Pre-Rolls

Seven years, he did this—2,500 days and change—all for the two pre-rolls that can be purchased legally in California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, and Nevada for about $7 apiece.

I did what I could at the time. I wrote to the governor. I set up a web page for Noble. I continued to call when I could, but the Louisiana Department of Corrections kept transferring Noble from one parish prison to another, and it was hard to keep track of him. It was also, I’ll confess, hard to keep talking to Noble when I knew I could offer him almost no hope. Eventually we stopped talking altogether.

My book was published, I went on tour, I talked about Noble and read passages about his case at public readings. When I got to the part about the 13-year sentence, some audience members audibly gasped. A few people, I remember, blurted out Oh, no! Meanwhile, Noble stood behind bars and tried to keep away from the crazy ones.

Other writers and other outlets publicized Noble’s case. 60 Minutes broadcast a segment that shamed Gov. Bobby Jindal, District Attorney Cannizzaro, and the state of Louisiana. But they didn’t care. Outsiders don’t vote.

Lawyer Stuck With Him

Fortunately, Bernard Noble found a lawyer who stuck with the case. Jee Park, an attorney in the Orleans Public Defender’s office, kept Noble’s file open, year after year. She won him a new sentencing hearing. In December 2016, After nearly a year of negotiation with the Orleans Parish District Attorney, the DA agreed to reduce Noble’s sentence to eight years and make him eligible for parole.

Last year Park left the public defender’s office to become a senior attorney with Innocence Project New Orleans (IPNO), a nonprofit law office that represents innocent and overincarcerated prisoners serving sentences in Louisiana and Mississippi. Since its founding in 2001, IPNO has freed or exonerated 30 innocent men.

Yesterday, Park sent this email to Bernard Noble’s supporters:

“The last time I reached out to you in December 2016, I let you know that Bernard Noble was re-sentenced. Today, I write with even better news. He was granted parole yesterday.

I am still working out the logistics of his release but our hope and goal is to get him back to his children and family in the next few days.

Thank you all for your sustained interest in and support of Bernard and his case over the years. Under his original sentence, he would have been home in 2025, but he now gets to be with his children, his aging mother, and the rest of his family.

His case exemplifies the injustice and cruelty of our drug sentencing laws and how habitual offender statutes can be applied selectively and unfairly.

It has not been easy for Bernard, being apart from his children [all] these years, but he never gave up hope that he would be home before the end of his 13+ year sentence. With grace and determination, Bernard has persevered.”

Bernard has persevered. He reminds the rest of us that we need to persevere as well. There are many more Bernard Nobles still in prison, and tens of thousands who’ve done their time but now deal with the lifelong repercussions of our misguided and cruel drug laws. There was news out of California and Colorado this week that state and county officials are moving to expunge the records of those caught up in the cannabis hysteria of a past era. Eventually, I expect we’ll hear similar news from Louisiana. And I hope they move Bernard Noble to the front of the line.