A new crackdown has begun in California’s cannabis growing heartland of Humboldt County. For unlicensed farmers, a summer of reckoning has arrived.

Now that local and state authorities have provisionally licensed about 1,500 legal cannabis farms statewide, they’re stepping up enforcement actions against farmers growing without a permit. County officials are doing it not with SWAT team raids, but by enforcing a laundry list of civil codes. And it’s having an effect. Civil code enforcement is decimating California’s legacy cannabis growers like criminal prohibition never could.

“It’s having a pretty strong deterrent effect because people don’t want to lose everything they’ve worked for—mainly their property.”

Fines of $10,000 per day, per violation—maxing out at $900,000, followed by property liens and forfeiture—have replaced traditional fears of a sheriff’s raid in Humboldt this summer.

Officials tell Leafly the Humboldt County Planning and Building Department has sent out 148 cannabis-related “Notices to Abate” to property owners so far in 2019. The county sent 597 abatement notices in 2018.

Recipients have ten days to remove their plants or they face record fines—far higher than monetary penalties enacted against any other business type. If you chop down your plants the same day you get the notice, you face a minimum $10,000 fine on your property. If you don’t, fines can run up to 90 days, totaling $900,000, followed by a county collection action, and potential loss of the property.

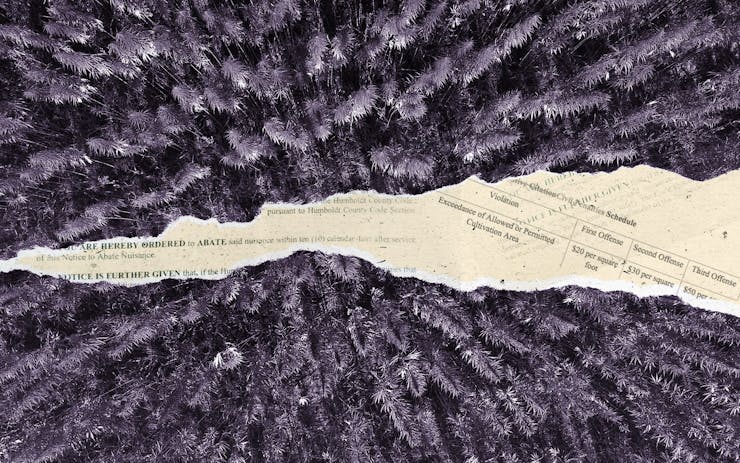

A notice to abate recently posted on an unlicensed Humboldt County cannabis farm. (Photo courtesy of Redheaded Blackbelt)

The results speak for themselves. Humboldt County has assessed $3.28 million in cannabis abatement fines for the years 2018 and 2019. So far, 376 cannabis-related code violations have been abated or are in the process of being abated. The county has filed liens on five properties.

Longtime criminal defense attorney Omar Figueroa says civil code enforcers armed with satellite imagery have changed the decades-old game of cannabis farmer whack-a-mole. County officials spot tiny grow structures from space using satellite images, and then send abatement notices to any property without a cultivation license.Ready to Shop Legal Cannabis?“It’s having a pretty strong deterrent effect because people don’t want to lose everything they’ve worked for—mainly their property,” Figueroa says. “Humboldt used to be a place you could hide under the trees, but with satellite mapping it’s much more challenging to have an unpermitted cannabis grow.”

Same in Sonoma County

A similar dynamic is playing out in another legacy cannabis-growing center, Sonoma County, just north of San Francisco. Attorney Joe Rogoway doesn’t even do criminal work anymore. He represents clients facing “seven-figure” fines who’ve stopped growing in Sonoma County. Sonoma County has issued $1.77 million in cannabis civil fines to date for the years 2018 and 2019.

“It’s stopping them,” Rogoway tells Leafly. “They don’t have a choice. It’s $10,000 per day. Sonoma County has just been rabid with all this—it’s been terrible.”

Looking For Legal Cannabis? Leafly Has All Your Local Menus

Second Wave: Retail Stores

Illegal retail stores are next. A cannabis regulations law—AB 97—passed July 1 in Sacramento and creates $30,000 fines, per day, for operating an illegal storefront. The fines are designed to target the hundreds of illegal stores competing against the legal ones in Los Angeles.

“At its core, the war on drugs isn’t necessarily over. It’s being civilized.”

This dynamic—swift, punitive civil fines replacing lengthy criminal trials—constitutes a new phase in the 80-year-old war on marijuana. Scofflaws don’t face trial and prison. Instead, county officials bankrupt them and confiscate their properties.

Joe Rogoway has worked criminal cases in 16 counties for almost two decades. “I never saw this type of zealous enforcement that is happening,” he says. “There was enforcement, but this sort of systemic way of addressing cultivation is just much more pernicious and harmful to cannabis cultivators than prohibition was.”

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries near“At its core, the war on drugs isn’t necessarily over,” says Hezekiah Allen, former executive director of the California Growers Association. “It’s being civilized.”

Not Your Grandfather’s Drug War

Legalization in California has ushered in a reckoning for cannabis growers who’ve long flouted local land use codes.

Beginning in the 1980s, California became the number one domestic grower of cannabis in the United States. With the 1996 passage of medical legalization—and then the adoption of Senate Bill 420 in 2012—the quasi-legal medical cannabis trade ramped up to a multi-billion-dollar industry.

But in 2013, the California Supreme Court declared that cities and counties need not tolerate any personal or commercial cannabis activity at all—even a medical patient growing a single plant. The police powers of cities and counties were further bolstered by the California Legislature’s adoption of medical cannabis regulations in 2015, and the voter-approved adult-use initiative, Prop. 64, in 2016.

Plenty of Demand Out of State

According to data compiled by CannaRegs, today about 280 California jurisdictions allow some form of commercial cannabis cultivation. But it can take two years and $2 million to get a grow permit, said Rogoway. While the number of licensed farms is climbing, the illicit market remains vastly bigger. About four out of every five pounds of cannabis grown in the state heads east to feed illicit markets, experts think.

Those growing without permits violate multiple new local and state civil codes, and they face a new enforcement regime that’s better staffed, better financed, and on better legal footing than police. The traditional layer cake of enforcement—with your typical sheriffs and Drug Enforcement Administration agents—has been fattened by a much thicker layer of county code enforcement officers, plus Department of Fish and Wildlife officers, State Water Resources Control Board officers, and more.

“The irony is now that it’s legal, it’s more illegal than ever, because more agencies have legal authorization to come after you,” says Swami Chaitanya, licensed grower of Swami Select in neighboring Mendocino County. “It’s devastating to the Humboldt community.”

“There are like 10 or 15 different agencies, they have lots of money, and they are spending lots of money,” says Chaitanya. “They all have the budgets to do it, and they’ve been chomping at the bit to get at this.”

Civil Is Quicker, Cheaper, More Effective Than Criminal

Legalization has plenty of old-school farmers pining for the good old days of running from DEA helicopters and the local sheriff. At least then you had some rights. Civil cases are far faster, cheaper, easier, and more effective to pursue.

Many longtime criminal defense attorneys have almost totally switched to regulatory work and civil cases. Veteran attorney Bill Panzer says his practice representing criminal cannabis defendants, “has taken a big hit over the last two years.”

“When you’re talking about criminal cases, you’ve got all these constitutional rights and statutory rights as a person who is presumed innocent. The burden is on the government, the people, to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a crime has been committed,” Panzer says. “When you got a civil case, you don’t have all these constitutional protections, and the burden of proof is a preponderance of evidence, more often than not.”

The timing is truncated, too. Criminal defendants can drag cases out for years to their benefit. Civil code violators have ten days to appeal a notice to abate. Appeal hearings are swift and involve no jury, no judge, and loose rules on evidence. “It’s very informal,” says Rogoway.

Civil abatement is also cost effective, Panzer notes. Sending out 100 threatening abatement letters might cost $49 in stamps, versus millions of dollars in police overtime for raids.

“Even if only five or ten guys go, ‘Holy shit!’ and pull out their crop, that’s a lot cheaper than sending cops out to bust people and drag them through the court system,” Panzer says. “It’s a lot easier to hit them in the pocketbook.”

In June, the Santa Barbara County Sheriff seized 20 tons of illegal cannabis in a four-day raid following a two-month investigation. The Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office also destroyed 350,000 cannabis plants from the illegal grow outside Buellton. (Santa Barbara County Sheriff via AP)

Catching Bad Apples, and Good Ones

In the eyes of local and state officials, growing unlicensed cannabis is a noxious land use that damages and destroys streams and rivers, and kills off endangered species. It also undercuts everyone who’s paying through the nose to play by the rules, and jeopardizes the implementation of California’s legal system.

The Humboldt County cannabis abatement program has focused on southern Humboldt and the watersheds most devastated by decades of illicit growing: sections of Salmon Creek, Redwood Creek, and the Mattole River sucked dry by illicit megafarms.

Unpermitted structures on satellite maps draw code enforcement scrutiny. Once on the property, code enforcement officers cite unpermitted roadwork, grading, culverts, tree-cutting, stream fouling, junk cars, and sewage discharge.

Much of county’s work is to be cheered, says Hezekiah Allen.

“Watching family members dispose of junked cars by burying them in a landslide helped me become an environmentalist,” he said. “Some of that does need to be cleaned up.”

Swami Chaitanya is also happy that growers who are sucking streams dry finally face reprisal.

By contrast, he’s spent the last five years in discussions with the Department of Fish and Wildlife to get water permits, and he’s paid “lots of money” for engineers, geologists, and biologists.

“Prop. 64 incredibly overregulated the industry. They’re regulating it like it’s plutonium laced with cyanide.”

But blanket civil enforcement can catch both bad apples and good ones, Chaitanya says.

In both Humboldt and Sonoma County, locals say officials did not prioritize the biggest violators and then work their way down the list. Instead, they went after the little guys who failed the new, complex, expensive, and ever-changing permitting process.

“Prop. 64 incredibly overregulated the industry,” says Panzer. “They’re regulating it like it’s plutonium laced with cyanide.”

Licensed Southern Humboldt cannabis farmer and journalist Kym Kemp, who operates the local news blog Redheaded Blackbelt, says neighbors who have fruit and vegetable gardens have gotten abatement notices.

In her case, the Water Board saw her 8’X12’ winter veggie hoop house from orbit, showed her the photo, and told her to take it down.

“I don’t grasp why that would be the first place you would start when there’s a neighbor a quarter mile down the road who leveled a mountain,” she says.

Of the 200 or so cannabis grow license applicants in Sonoma County, just three or four have received final use permits, Rogoway says. Everybody else operates with temporary permits while stuck in license limbo.

“They’re in an entirely unworkable dynamic where they can’t progress. And then they’re being punished for their attempts at compliance,” says Rogoway. “It’s a real smack in the face.”

“There’s a lot of people who regret ever telling the county what they were doing and attempting to participate in the program,” Rogoway adds. “Those people would have been much better off if they had stayed in the black market.”

A Growing Diaspora

As it stands now, the traditional places where cannabis was grown for decades—Northern California counties—is not where most legal cannabis is grown. Mega-farms in Santa Barbara, indoor operations in cities, and remote facilities in the Southern California deserts have proven far more legally hospitable than the water-stressed hills of Humboldt, or the snobby wine country of Sonoma.

“For the most part the heritage farmers have already gone extinct,” says Rogoway.

That’s starting to hit other local merchants, as the illicit farming dollars that once circulated here have dried up. Humboldt County sales tax rolls were down 2% in 2018 while the average California county saw sales tax revenue rise 4%.

“I know hydroponics suppliers whose annual sales are off by millions of dollars,” says Kemp. “There are so many properties for sale because of the civil abatements. They’ve knocked out so many growers.”

“The people that historically have been cultivating, there just isn’t a place for them in a physical sense to continue to do so,” says Rogoway.

“It’s resulted in a cannabis diaspora of growers leaving [Humboldt] county and seeking greener pastures, because it’s so hostile,” adds Figueroa.

And civil enforcement is still just getting started.

This summer, Humboldt’s abatement program is scheduled to take root in neighboring Mendocino County. Other jurisdictions are following suit.

In Santa Barbara, a new task force now spends its time combing through license applications and comparing them with satellite images to spot potential license fraud, which is grounds for abatement. A single raid last month yielded 20 tons of unpermitted cannabis and 350,000 plants.

“There are structural features that give incentives to agencies to conduct enforcement, and once they get a taste of that money, it’s on,” says Figueroa.

Fines of $30,000 per day are also coming for unlicensed stores in Los Angeles—promising to change the old game for good.

[Editor’s Note: Update July 22, 2019 below:]

Sonoma County provided to Leafly an update on their cannabis civil abatement program. Sonoma County reports:

- The total number of cannabis-involved Notice to Abates issued by Sonoma County in 2019: 124

- The total number of cannabis-involved Notice to Abates issued by Sonoma County in 2018: 48

- The total amount of fines assessed for cannabis-involved Notice to Abates in 2019: $666,751 to date

- The total amount of fines assessed for cannabis-involved Notice to Abates in 2018: $1,104,000

- The sum amount of cannabis-involved Notice to Abate fines collected in 2019: $171,707

- The sum amount of cannabis-involved Notice to Abate fines collected in 2018: $835,344

- The total number of property liens derived from fines for cannabis-involved Notice to Abates in 2019 and 2018: Sonoma County does not put liens on properties for cannabis-involved civil abatement fines.