Erica Chittenden was barely breathing.

Lorincz called 911. Then he took the couple’s four-year-old son Dante to the boy’s room and told him to stay inside. Lorincz wanted to spare Dante the sight of his unconscious mother.

Paramedics arrived few minutes later. Patrick Gedeon, a deputy with the Ottawa County Sheriff’s Department, also responded to the call.

The paramedics helped Erica Chittenden regain consciousness. They worked with Lorincz (pronounced Lawrence) to figure out what happened. Chittenden struggled with bipolar disorder, and might have suffered an overdose of prescribed anti-anxiety drugs.

Deputy Gedeon scanned the kitchen to see what Chittenden could have taken. He spotted a small plastic pill bottle. Inside was a smudge of sticky brown material.

“Is this what I think it is?” the deputy asked Lorincz.

“What do you think it is?”

“Marijuana concentrate. BHO.”

“Yes,” said Lorincz. “It’s my medicine. I have a medical marijuana card.”

While paramedics moved Chittenden to an ambulance, Deputy Gedeon placed the BHO container in an evidence bag. Then he called the local child protective services (CPS) office.

“The whole thing was a nightmare. I didn't understand how they could take our child away.”

Lorincz didn’t register what the deputy was up to. When the CPS case worker arrived, Lorincz assumed she was there to help with his son while Lorincz followed his wife to North Ottawa Community Hospital.

But Gedeon had called CPS for a different, more distressing reason. Despite Max Lorincz’s state-issued medical marijuana card, Michigan law allows a police officer to proclaim a home a “drug house” if cannabis is used inside. When the CPS worker arrived, she removed Dante from his parents’ custody. The four-year-old boy spent the night with a foster family. Lorincz wasn’t arrested for cannabis that night. In effect, his four-year-old son was.

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries near“The whole thing was a nightmare,” Lorincz later recalled. “I didn’t understand how they could take our child away.”

Max Lorincz’s nightmare was only beginning. His original 911 call set off a chain of events that would eventually result in his own arrest and an 18-month battle for custody of Dante. It would also reveal a statewide conspiracy to tamper with evidence, distort science, and falsify criminal charges–all in an effort to strip Michigan’s 180,000 medical marijuana patients of their legal right to medicine.

Medical cannabis is legal in 25 states. But not every state offers equal protection to patients. In places like Michigan, some law enforcement leaders continue to see medical marijuana patients as a bunch of stoners hiding behind the shield of a half-baked law–and state officials are actively undermining those protections. Over the past three years, leaders of the Michigan State Police pressured crime lab scientists to falsely classify medical cannabis as a synthetic drug, putting more than 180,000 patients at risk of felony arrest. Almost nobody outside the crime lab knew it was happening.

And the worst part? The crime lab’s science-warping policy remains in effect today. Thousands of Michigan’s legally registered medical marijuana patients could be charged with possession of synthetic drugs, depending on the whim of the crime lab.

MMJ: Voters want it, prosecutors don’t

There’s a strange disconnect between Michigan’s citizens and the law enforcement officials they employ. As voters have expressed increasing support for cannabis legalization, police are arresting more and more consumers. In the past five years, 22 Michigan cities have voted to decriminalize cannabis.

Max Lorincz is among the 92 percent of Michigan MMJ patients who list severe and chronic pain as a qualifying condition. Chronic pain from two herniated disks put Lorincz on an opioid regimen so heavy that he suffered kidney failure. In 2009, a doctor recommended he try medical marijuana instead. Since then, he’s used cannabis to wean himself off opioids and improve his health.

Although medical marijuana enjoys widespread support here, many law enforcement officials have never accepted it. In 2012, Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette began raiding and shutting down dispensaries, but he never questioned the right of patients to possess medicine. Which is why Max Lorincz didn’t expect to be charged with a crime. He had his medical marijuana card. And he possessed far less than the legal limit.

Local Decriminalization in Michigan

| Passed | Failed |

|---|---|

| Detroit | Frankfort |

| Grand Rapids | Clare |

| Lansing | Harrison |

| Flint | Lapeer |

| Kalamazoo | Onaway |

| Saginaw | Montrose |

| Port Huron | |

| East Lansing | |

| Mount Pleasant | |

| Ypsilanti | |

| Berkeley | |

| Hazel Park | |

| Huntington Woods | |

| Oak Park | |

| Pleasant Ridge | |

| Portage |

For three months, Lorincz remained uncharged. Four-year-old Dante, meanwhile, remained trapped in the state’s foster care system. The state of Michigan had, in effect, kidnapped the couple’s son. Dante was assigned to Bethany Christian Services, a faith-based organization known for its conservative culture. The agency’s president recently wrote that “we [at Bethany] adhere to the values and beliefs of our faith when serving.” Those beliefs include prohibiting adoption by same-sex couples and, apparently, refusing to allow a parent to legally medicate with cannabis. In order to see his son in weekly two-hour supervised visits, Lorincz had to stop taking medical cannabis and pass drug tests showing no cannabis use. To do that, he was forced to return to opioids.

Then in early January 2015, out of the blue, Lorincz was arrested and charged with misdemeanor marijuana possession. For what? he asked. For the vial Deputy Gedeon found back in September, he was told.

Since when did a registered medical marijuana patient merit a two-year sentence for Spice? How was that even possible?

Lorincz was confused. “Have these people not read the Michigan Medical Marihuana Act?” he wondered.

Most cases like this never to go trial. The defendant usually pleads to a lesser charge and moves on. Lorincz’s public defender advised him to cut a deal. But Lorincz refused to plead.

“I was willing to fight because I hadn’t done anything wrong,” he told Leafly.

Here’s the key moment in the case, one that would grow in significance only in hindsight. When Lorincz refused to plead, Ottawa County Prosecutor Ronald Frantz threatened to charge him with possession of synthetic THC, a felony that came with a two-year prison sentence.

The threat baffled Lorincz. Since when did a registered medical marijuana patient merit a two-year sentence for K2 or Spice? How was that even possible?

The answer could be found in the files of the Michigan State Crime Lab.

Crime labs in the public eye

Crime labs aren’t in the perfection business. The past decade has witnessed a surge of scandals involving falsified reports, tainted studies, and missing evidence. Last year Slate legal affairs writer Dahlia Lithwick chronicled the problem in a piece titled, “Crime Lab Scandals Keep Getting Worse.”

Lithwick noted the key role played by the war on drugs:

“Over the past decade, crime lab scandals have plagued at least 20 states, as well as the FBI. We know that one of the unintended consequences of the war on drugs has been a rush to prosecute and convict and that crime labs have not operated with sufficient independence from prosecutors’ offices in many instances… Years of deliberate falsification have ruined thousands of lives.”

The Michigan State Crime Lab, a division of the Michigan State Police Department, maintains a number of labs across the state. Each lab handles evidence from many different police agencies.

After Deputy Gedeon bagged Max Lorincz’s medicine vial on Sept. 24, he transferred it to the Michigan State Police Forensic Laboratory in nearby Grand Rapids. There it remained in storage until Dec. 29, when William Ruhf, a senior forensic scientist, finally got around to analyzing it.

Using a gas chromatographic mass spectrometer, Ruhf identified the presence of THC in the residue. On his report, he wrote “Delta-1 THC, origin unknown.”

That designation puzzled Michael Komorn.

“I’d never had a case where the prosecutor didn’t charge for marijuana.”

Komorn is a criminal defense attorney based in Farmington Hills, outside Detroit. As president of the Michigan Medical Marijuana Association, he’s a leading expert on the state’s MMJ law. He was alerted to Max Lorincz’s case by Dana Chicklas, a reporter for Fox 17 News in Grand Rapids, who discovered the story and refused to let it die.

Komorn thought Lorincz’s predicament might have implications for many of his clients, as well as 180,000 patients statewide. He offered to take on Lorincz’s case pro bono.

Komorn had never seen an MMJ patient hit with a felony synthetics charge. “That seemed very strange to me,” Komorn told Leafly. “I’d never had a case where the prosecutor didn’t charge for marijuana.” In other words, it seemed to Komorn that the state was arguing that Lorincz’s marijuana wasn’t actually marijuana.

At a preliminary hearing in April 2015, Komorn finally got a chance to unravel this Kafka-esque tangle. Questioning William Ruhf, the scientist who analyzed the BHO smear, Komorn asked him why he wrote “origin unknown” on his report.

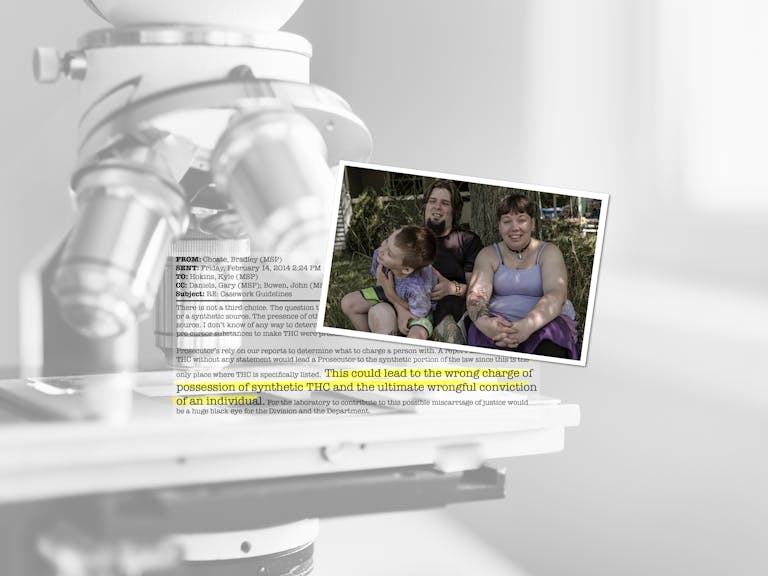

Defense attorney Michael Komorn suspected the “policy change” could put the state’s 180,000 medical cannabis patients at risk. (Courtesy of Michael Komorn)

“That means that I do not know where [the THC] originated from,” Ruhf said, according to the court transcript. Because it’s possible to synthetically manufacture THC, Ruhf added, he couldn’t say for certain that the THC found in the residue originated in a cannabis plant.

Isn’t there some way you could test that? Komorn wondered.

No, said Ruhf. “There is nothing to my knowledge scientifically that can be done to demonstrate a simple molecule of THC, whether it originated from a plant” or a synthetic process. “It all looks the same chemically with respect to the instruments and how it’s analyzed.”

Because of a recent policy change, Ruhf said, lab analysts add the phrase “origin unknown” in cases where they don’t see any plant material. Ruhf called it “a clarification.”

Komorn didn’t get it. “You’ve got the same material, same person doing the test, same variables,” he recalled. “Why did this policy change?”

With Lorincz now facing two years in prison and the permanent loss of his son, Komorn sensed that this case might be an indication of a much larger and more troubling scheme. Prosecutors were no longer playing by the rules established by voters and the courts. If this change had become policy, Michigan’s 180,000 medical marijuana patients and 33,000 caregivers were now risking felony prison time—and none of them knew it.

Playing a hunch, Komorn filed a Freedom of Information Act request asking for all State Crime Lab emails related to a marijuana policy change.

What he received, weeks later, astonished him. “I thought that some manipulation might have taken place,” Komorn recalled. “But not to the extent revealed in the emails. They took people who wouldn’t normally be arrested, and made them subject to felonies and forfeiture. And in Max’s case, it led to the loss of his son.”

Internal emails tell the tale

Michaud’s email directed lab staff to consult with Ken Stecker, a lobbyist for the state’s prosecutors, who would rule on cannabis policy.

So what happened?

It had to do with a law the state legislature passed in late 2012. Concerned about the spread of K2, Spice, and other drugs that contain synthetic THC, state lawmakers enacted tough new penalties against the compounds. The law had nothing to do with medical marijuana. But within months, police officials and prosecutors realized that if they could legally decouple THC from the cannabis plant, they could charge medical marijuana patients with possession of synthetics under the new law—and destroy the legal protections afforded to patients under the Michigan Medical Marihuana Act.

That is, law enforcement wanted to treat any cannabis product that didn’t appear in plant form as the legal equivalent of Spice or K2. And they wanted to do secretly.

So the Michigan State Crime Lab quietly instituted a new policy. If no actual cannabis leaf was present, lab analysts were told to record the drug as “THC—origin unknown.” That “clarification” allowed prosecutors to charge medical marijuana patients with felony possession of synthetic THC.

Though it represented a radical change in the law, few outside the lab were aware of the new policy. The public was never informed. State legislators were never made aware.

Komorn couldn't believe his eyes. A traffic safety specialist for a lobbying group had become the secret cannabis czar of the Michigan State Crime Lab.

Inside the lab, some balked at the change. In a May 2013 email uncovered by Komorn, an analyst named Scott Penabaker, who worked at the lab in Northville, told colleagues that he found it “highly doubtful than any of these Med. Mari. products we are seeing have THC that was synthesized. This would be completely impractical. We are mostly likely seeing naturally occurring THC extracted from the plant!”

The result, Penabaker wrote, was that “you now jump from a misdemeanor to a felony charge.”

What’s more, Komorn discovered, this new policy didn’t even originate from within the state’s law enforcement agencies.

On July 25, 2013, Capt. Greg Michaud, Director of the Michigan State Police’s Forensic Science Division received a memo from a well-known cannabis prohibitionist named Ken Stecker. Stecker’s email claimed that edibles made with cannabis extracts did not qualify as “usable marihuana” under the Medical Marihuana Act.

This email pertained to another case, but it laid the legal groundwork for the prosecution against Max Lorincz. “By possessing edibles that were not ‘usable marihuana’ under the MMMA, but that indisputably were ‘marihuana,’ [the defendant] failed to meet the requirement for section 4 immunity,” Stecker wrote.

“Section 4” of Michigan’s medical marijuana law spells out the legal protections afforded to patients. By tweaking its definition of “usable marihuana,” Stecker implied, the crime lab could effectively scuttle those protections.

This was yet another odd turn in the increasingly bizarre war against Michigan’s medical marijuana patients. Ken Stecker is not an elected official. He’s a $105,000-a-year traffic safety specialist for PAAM, the Prosecuting Attorneys Association of Michigan, a trade association that runs education programs and lobbies the legislature on behalf of county prosecutors.

Stecker’s power and influence belies his job title. For years he’s been Michigan’s prohibitionist-in-chief. Since 2008, he’s given dozens of presentations around the state denouncing medical marijuana. During testimony before a legislative committee last year, a PAAM official described Stecker as “our leading individual as far as the technical nature of the medical marijuana act is concerned.”

Less than an hour after receiving the email from lobbyist Ken Stecker, Crime Lab Director Michaud relayed an order to regional crime lab managers around the state that turned Stecker’s proposal into official policy.

“In my meeting with PAAM today,” Michaud wrote, “it was decided that any questions regarding law interpretation (e.g., recent controlled substances cases) will be directed thru the applicable Technical Leader who will then reach out to Mr. Ken Stecker for a proper interpretation.”

Michael Komorn could scarcely believe what he was reading. Thanks to Michaud’s order, a traffic safety specialist for a trade association had become the clandestine cannabis czar of the Michigan State Crime Lab.

More scientists push back

By early 2014, Komorn’s trove of FOIA’d emails would show, crime lab analysts were increasingly worried about the ethical implications of Stecker’s policy. Bradley Choate, supervisor of the Controlled Substances Unit in Lansing, voiced his concern. “I disagree with the changes,” he wrote in an email. “When THC is identified in a case, [lab analysts have] two choices.” They can, he explained, identify it as marijuana, which is a misdemeanor. Or they can identify it as synthetic THC, a felony. “There is not a third choice.”

Though lab analyst William Ruhf would later testify that it was impossible to differentiate between natural THC and synthetics, Choate noted that this was simply not true. In fact, it could be done with a few easy tests. The crime lab regularly purchased synthetic marijuana reference standards from Cayman Chemicals in Ann Arbor, in order to confirm that K2 or spice obtained in an arrest was, in fact, synthetic. “If we couldn’t purchase standards, we wouldn’t be able to make the (synthetic) identification,” State Crime Lab analyst Kyle Ann Hoskins told the Detroit Free Press in 2012.

One lab analyst testified that it was impossible to sort natural THC from synthetic. Another analyst noted that was simply not true.

In addition, the presence of other cannabinoids like CBD or CBN in the same sample “indicates that the substance is from a natural source,” Choate noted.

That is, the Michigan crime lab possessed tests to determine the THC’s origin in seized materials. But under the Stecker policy, analysts were forbidden from reporting anything beyond the presence of THC. By doing so, they handed prosecutors a powerful weapon they could use to convince defendants to plead quickly to a marijuana charge: the threat of a felony synthetics charge.

The stakes were clear. A lab report adhering to the Stecker policy “could lead to the wrong charge of possession of synthetic THC and the ultimate wrongful conviction of an individual,” wrote lab analyst Choate. “For the laboratory to contribute to this possible miscarriage of justice would be a huge black eye,” he added.

This wasn’t a squabble over a minor policy tweak. In 2014, Michigan law enforcement agencies made more than 23,000 cannabis arrests. Forensic Science Division Director Michaud once estimated that 40 percent of the crime lab’s $60 million annual budget was spent on cannabis testing.

Choate’s colleagues tried to craft an artful phrase that would carry out Stecker’s policy without violating their own ethical boundaries. One analyst suggested “The origin of the THC identified whether from a plant extract (marihuana) or a synthetic source could not be determined.”

Which is technically true. But that’s like reporting that it “could not be determined” if a homicide suspect touched the murder weapon, while concealing the fact that the crime lab chose not to dust for fingerprints.

The stakes were clear. The new lab policy could lead to “the ultimate wrongful conviction of an individual.”

On March 15, 2014, Choate’s superiors effectively quashed the discussion. John Bowen, crime lab director Greg Michaud’s chief of staff, declared that the policy had been decided, period. For medical marijuana patients in Michigan, no leaf meant no immunity.

“Is it likely that someone went to the trouble to manufacture THC and two other cannabinoids, mix them up, and bake them into a pan of brownies?” Bowen wrote. “Of course not. That doesn’t mean we should change the results to show we found Marijuana. We didn’t, because Marijuana is a plant, and we didn’t find plant parts.”

“I do not intend to bring Ken Stecker in to explain this to our drug unit,” Bowen wrote testily; “I think everyone understands the issue pretty clearly.”

Bowen gave marching orders to the crime lab analysts. “If we found THC, with no other plant parts,” he wrote, “we should report it as THC, not Marijuana.”

And there the policy remained, up to and past September 24, 2014, the day Max Lorincz called 911 to attend to his wife Erica on the kitchen floor.

Risking perjury

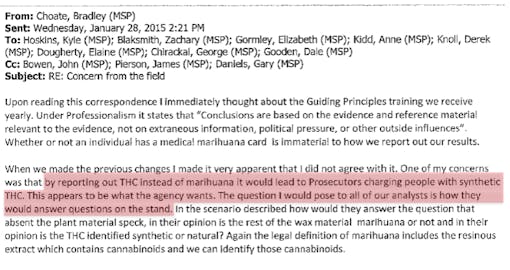

Lab analyst Bradley Choate found the false-synthetics policy at odds with the lab’s ethics training.

Bowen’s orders settled the policy question, but it didn’t shield lab analysts from the risk of perjury.

In late January 2015, not long after Max Lorincz’s arrest, analyst Bradley Choate reiterated his concern that reporting THC instead of marijuana, “would lead prosecutors to charge people with synthetic THC. This appears to be what the agency wants.” Choate worried that lab analysts might be forced to lie if they were called to testify in one of these cases. “The question I would pose to all of our analysts is how they would answer questions on the stand.”

A few weeks after Choate sent that email, his colleague William Ruhf found himself on the stand answering questions from Max Lorincz’s lawyer.

Ruhf stuck to the playbook. He said he didn’t know the origin of the THC, and didn’t have the means to determine whether it “originated from a plant or from the manufacture of a synthetic route synthesis, if you will, within a laboratory. It all looks the same chemically with respect to the instruments and how it’s analyzed.”

A child pays for the policy

The gathering evidence against the crime lab did little to lighten the ordeal of Max Lorincz, Erica Chittenden, and their son Dante.

Caught in the byzantine bureaucracy of the state foster care system, Dante spent Christmas with a foster family. When his fifth birthday came around in May, Dante was denied a brief parental visit because the state caseworker deemed medical marijuana—even though Max had stopped taking it—a threat to the child’s safety. “I tried to explain to her that the form I took when I was around my son is non-intoxicating, there’s no high or buzz,” Max Lorincz recalled. “She had a strong agenda against marijuana and refused to believe there could be any possible positive use of it.”

Dante would ask when he could come home. 'You'll have to wait just a little longer,' his dad said

The Lorincz family dealt with a revolving door of caseworkers. One was fired; another quit; the case got continually reassigned. “Each time, the paperwork would get lost and we’d have to start over from scratch,” Lorincz recalled. “At one point a caseworker argued in court that Dante should be put up for adoption because the parental bond had been broken—because he’d been out of our custody for so long!”

During brief supervised visits with his parents (sometimes once a week, sometimes twice), Dante would ask when he could come home. “Every time we had to tell him he had to wait just a little bit longer,” Lorincz recalled.

That September, Dante started kindergarten. Due to the court order, his mother and father could not be there. Five-year-old Dante was dropped off for his first day at school by a foster parent.

“Perverted science. Broke the law.”

In October 2015, Max Lorincz’s lawyer vented the full extent of his outrage.

In an extraordinary court filing, Michael Komorn accused the Michigan State Crime Lab of suborning and committing perjury. “The crime lab engaged in systematic evidence tampering,” he wrote. “The crime lab perverted science and broke the law. It reported bogus crimes.”

“The Crime Lab was transformed into a Crime Factory” that stripped away the rights guaranteed to 180,000 patients and caregivers across the state. As evidence he offered the words of crime lab officials themselves, circulated via email.

The Michigan State Police responded by defending its secretly altered cannabis policy. The changes, the department stated, were made “in an effort to standardize reporting practices among our laboratories and to ensure laboratory reports only include findings that can be proved scientifically.”

“The Crime Lab was transformed into a Crime Factory.”

Komorn wondered if other cases had been affected by the “THC—origin unknown” fraud. He found plenty. Brandon Shobe, a registered medical marijuana caregiver from Highland Park, north of Detroit, was arrested and charged based on a forensic lab report of THC that “may be from a plant or a synthetic source.” Jason Poe, a medical marijuana patient, was arrested for cannabis possession but faces the possibility of a felony charge for synthetic THC because of the lab report. Earl Carruthers, a registered medical marijuana patient and former Wayne State University football player who cracked his pelvis during his playing days, also faces a potential felony charge for synthetic THC, based on a faulty lab report.

Those patients were harmed by the crime lab’s changed policy, a change “made in an attempt to strip medical marijuana patients of their rights and immunities,” wrote Komorn, “charge or threaten to charge citizens with greater crimes than they might have committed, obtain plea deals, and increase proceeds from drug forfeiture.”

Other police agencies doubled down against the accusations. Oakland County Sheriff Michael Bouchard, whose deputies arrested Earl Carruthers, described Komorn’s charges as “garbage.”

The crime lab’s ex-director told Chicklas why he quit: pressure to be “in the conviction business” instead of practicing solid science.

Those familiar with the crime lab, however, sang a different song. A few days after Komorn aired his accusations, former Michigan State Police Forensic Science Director John Collins went public in an interview with Fox 17’s Dana Chicklas. Collins resigned in 2012, he said, because the pressure to produce results favoring prosecutors became too much to bear. “It was just a non-stop political game that really got frustrating, and it wore down the morale of our staff, and it quite honestly, it wore me down,” he told Chicklas. Collins fought “to let people understand that our laboratories were not in the prosecution business, they’re not in the conviction business, they’re in the science business,” he said.

That did not go over well with his superiors, and eventually led to his departure. When Collins left, his position was filled by Capt. Greg Michaud, the man who would turn the Ken Stecker memo into official policy.

Vindication in court

Despite Komorn’s growing body of evidence, Ottawa County Prosecutor Ronald Frantz refused to drop the felony synthetics charge against Max Lorincz. “There is no conspiracy to overcharge MMA card holders,” Frantz said in an issued statement, “but rather a legal question of statutory interpretation.”

Frantz waved off Komorn’s accusations against the state crime lab. “The various defense allegations of lab agent misconduct, etc. are not relevant to the issue presently before the court,” he wrote.

“I haven't been willing to take a plea deal, because I didn't do anything wrong.”

Frantz’s statement would prove to be a misreading of the situation. Ottawa County Circuit Court Judge Ed Post found the crime lab allegations to be quite relevant. On January 22, 2016, Post quickly and quietly granted Komorn’s motion to quash the case against Max Lorincz. The evidence, the judge said, was insufficient to support the charge.

“It’s been a long 16 months,” Lorincz said after the dismissal. “It’s just nice to have it over.”

“From the very beginning I haven’t been willing to take a plea deal or anything, because I didn’t do anything wrong,” he added. “We’ve always medicated properly, and tried to make sure that we’re doing everything right.”

On her way out of the courthouse, assistant prosecutor Karen Miedema told FOX 17 reporter Dana Chicklas that her office hadn’t ruled out the possibility of re-filing misdeameanor marijuana possession charges against Max Lorincz.

Piecing the family back together

Even after the charge was dismissed, Max Lorincz still had to fight to repair his family’s shattered life.

In a saga that deserves its own twisted narrative, Lorincz and his wife Erica spent a year and a half struggling to regain custody of their young son Dante. Their case file was passed between five different child welfareworkers. Some quit. Others actively worked to break up the family. “Every time a new one received our case, we’d have to start over from the beginning,” Lorincz told Leafly. “Often our files would mysteriously go missing.”

“I believe they were purposely losing our files, assuming we’d mess up and forfeit our child permanently.”

“I believe they were purposely losing our files,” Lorincz said, “assuming that somewhere along the way we’d mess up and do something to forfeit our child permanently.” Lorincz and his wife were subjected to constant drug testing. He was legally barred from using medical marijuana, and was forced to return to muscle relaxants and opiods to deal with his chronic pain.

Finally, on March 25, 2016, five-year-old Dante was returned to his parents.

“It was near Easter,” Lorincz recalled. “We went out to dinner that night, and we tried to do a kind of birthday celebration,” to make up for the birthday they missed the previous year, which Dante spent in foster care. “We had a lot of colored eggs, and spent the evening playing with Skylanders, which are Dante’s favorite toys.”

Today, the Lorincz family is whole once more. Max is once again off opioids and managing his chronic pain with controlled doses of medical cannabis.

The false-felony policy remains

Max Lorincz’s ordeal has become the basis for a federal lawsuit. (Sean Proctor for Leafly)

Have reforms followed in the wake of the crime lab’s exposure? Not really.

Earlier this month the Michigan legislature passed the most significant medical cannabis reform package since the original passage of the 2008 Medical Marijuana Act. The legislation specifically allows patients to possess non-leaf forms of cannabis, such as edibles and concentrates.

But the state crime lab’s false-synthetics policy undermines the new reforms. The forensic division still requires its lab reports to state “the origin of [THC] may be from a plant (marijuana) or a synthetic source,” thereby allowing prosecutors to file or threaten false synthetics charges against legally registered medical marijuana patients.

Furthermore, nobody from the Michigan State Police Department or its forensic division has faced anything other than embarrassment from local media reports. Ken Stecker remains employed by PAAM, the Prosecuting Attorneys Association of Michigan. William Ruhf still works at the Lansing office of the state crime lab. Forensic Science Division Director Greg Michaud, who installed Stecker’s false felony policy, retired in May 2016.

“The crime lab is still doing this,” said Komorn. The false-synthetics policy leaves 180,000 MMJ patients exposed to possible arrest.

Leafly contacted the Michigan State Police to ask if changes in the policy were planned. The agency’s public affairs office responded by sending us a statement from November 17, 2015 “that explains our position reference (sic) these allegations.”

“The MSP-FSD [Michigan State Police Forensic Science Division] takes full responsibility for this policy change and stands behind its decision, as being in the best interest of science,” the statement read. “The allegation that politics or other influence played a role in this policy change is wholly untrue.”

In 2014, there were 35,762 drug arrests in Michigan. Last year there were 36,686. Approximately two-thirds of those arrests were for cannabis, and 85 percent of all cannabis arrests were for simple possession. Max Lorincz was one of 696 people arrested for marijuana possession in Ottawa County in 2014.

Mike Nichols, an adjunct professor of forensic science in criminal law at Western Michigan University, has formally asked the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate the actions of the Michigan State Police Crime Lab in its handling of marijuana cases. To date, the U.S. Justice Department has taken no official action on the request.

Meanwhile, Michael Komorn, Lorincz’s attorney, has filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of Lorincz and other MMJ patients. Komorn has asked the U.S. District Court to order a halt to the false lab reports, and to appoint a federal monitor to assure compliance. “The crime lab is still doing this,” despite the exposure and bad publicity, Komorn said earlier this month. “On any given day, an analyst could say a substance is marijuana. The next day they could say it’s ‘THC, origin unknown.'”

The first hearing in that lawsuit is scheduled for Nov. 2.

Featured images: Sean Proctor for Leafly