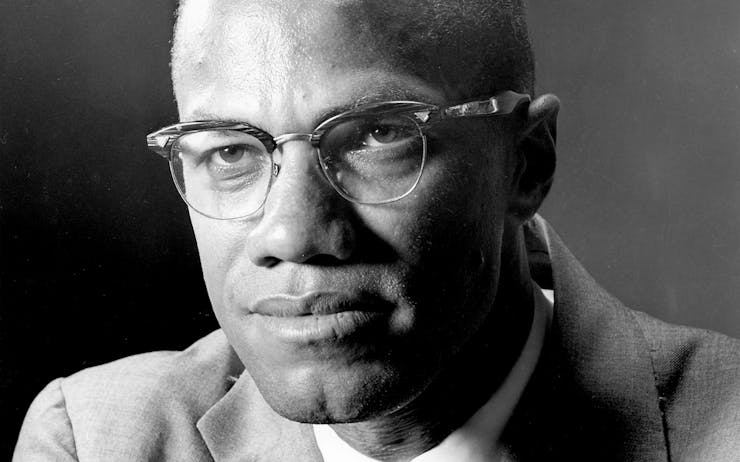

Malcolm X was an important figure in American history, known for his passionate advocacy for Black Americans during the Civil Rights Movement. But little is known about the iconic leaders love of cannabis, or “reefer,” as it was commonly called in his days in Harlem as a young man.

Keep reading to reflect on Malcolm’s experience with cannabis and the indelible impact of his legacy on America.

Born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm X was the fourth of seven children to Granada-born Louise Little, and Georgia-born Earl Little, an outspoken Baptist speaker. Both Louise and Earl were known to be followers of Marcus Garvey, political leader of the Pan-African movement. Earl’s activities caused backlash and, although the family relocated multiple times, he continued to be harassed by the Black Legion, a White Supremacist hate group. When Malcolm was six years old, his father was killed by what was ruled a streetcar accident, but the incident had all the hallmarks of a hate crime–he was tied to the railroad tracks and struck by a train.

His mother Louise later had a nervous breakdown and was committed to a state institution, while her children went into foster care. Malcolm bounced around for a time, riding the rails from Michigan to Boston, where his half-sister lived, before eventually moving to New York City’s Harlem neighborhood.

“With alcohol or marijuana lightening my head, and that wild music wailing away on those portable record players, it didn't take long to loosen up the dancing instincts in my African heritage.”

The first time he tried “reefers” was mixed up in his hazy memories of dance parties at the Roseland Ballroom, shooting craps, playing cards, and betting with a pool hall friend named Shorty. “All of us would be in somebody’s place, usually one of the girls’, and we’d be turning on, the reefers making everybody’s head light, or the whisky aglow in our middles,” he wrote in his autobiography.

He described how he would use cannabis and alcohol to mask the embarrassment of his country upbringing, which he blamed for his secret humiliation–he couldn’t dance.

“Shorty would take me to groovy, frantic scenes in different chicks’ and cats’ pads, where with the lights and juke down mellow, everybody blew gage and juiced back and jumped… With alcohol or marijuana lightening my head, and that wild music wailing away on those portable record players, it didn’t take long to loosen up the dancing instincts in my African heritage,” he reminisced in his writing.

While trying to earn a living, Malcolm got involved in selling cannabis, often to musicians who “were the heaviest consistent market for reefers,” Malcolm concluded. “In every band, at least half of the musicians smoked reefers. I’m not going to list names…In one case, every man in one of the bands which is still famous was on marijuana.”

Although Malcolm was making good money, he soon caught the attention of local narcotics squad detectives. They began to harass him, frisking and searching him, despite his quick-thinking tactics. He would often discreetly carry weed rolled into “sticks,” or joints, and drop them inconspicuously if he thought he was being followed. The cops continued to follow him, searching his apartment without warning and forcing him to switch up his territory to avoid the narcotics force.

This anecdote occurred in the early 1940s, but, unfortunately, modern-day New York is not so very different. Black Americans are still four times more likely to be arrested for marijuana charges than white Americans, despite equal rates of usage. In New York in 2016 alone, Black citizens comprised 43% of all drug-related arrests, while white New Yorkers accounted for just 12% of drug arrests.

Of this racial inequity, Malcolm was keenly aware, but, being a bright young man, he simply jumped back on the railroad to escape the cops and took his show on the road.

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries near“I could travel all over the East Coast selling reefers among my friends who were on tour with their bands… Nobody had ever heard of a traveling reefer peddler,” he wrote.

As his hustles increased in scope, so did the stakes. Malcolm became increasingly involved in harder drugs and regularly carried guns. In his autobiography, one passage eerily portends the violent end of his life.

“Deep down, I actually believed that after living as fully as humanly possible, one should then die violently. I expected then, as I still expect today, to die at any time.”

“I expected then, as I still expect today, to die at any time. But then, I think I deliberately invited death in many, sometimes insane, ways…”

In 1946, he was convicted of burglary and sentenced to 10 years in prison, although he only served seven. During his time in prison, he was introduced to the Nation of Islam and the teachings of Elijah Muhammed. He became devoted to the Nation of Islam, rapidly ascending to the role of minister. He changed his last name from Little to X, to represent the unknown African name that was stolen from his ancestors.

After a Nation of Islam member was beaten by New York City police officers, Malcolm X spoke out, catching the attention of the FBI by encouraging Black Americans to cast off the shackles of racism by any means necessary.

After more than a decade as the face of the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X broke ties with Elijah Muhammed when he became disillusioned by the lack of response to LAPD racial violence and rumors of Elijah’s improper sexual escapades. He began receiving death threats almost immediately–a NOI leader ordered his car bombed, and political drawings depicted him decapitated. The Nation sued to have his home repossessed, but the night before the eviction hearing, the house was destroyed in a fire. Malcolm X had become a target.

During the controversy, Malcolm continued to grow spiritually. He travelled to Saudi Arabia to visit Mecca, the holiest city in the Islam faith. There he saw Muslim people of all shades worshipping together. The experience challenged the radical racial politics he adopted in America, reinforcing his decision to distance himself from the Nation of Islam.

After returning from Mecca, Malcolm X was assassinated by a former Nation of Islam member named Mujahid Abdul Halim on February 21, 1965. The NYPD and FBI framed two other NOI members for the murder at the time. They each served more than 20 years before a New York City judge dismissed their convictions in 2021.

“I expected then, as I still expect today, to die at any time. But then, I think I deliberately invited death in many, sometimes insane, ways… I am only facing the facts when I know that any moment of any day, or any night, could bring me death.”

He speculated on the nature of his death in his autobiography, and what his legacy would be.

“When I am dead–I say it that way because from the things I know, I do not expect to live long enough to read this book in its finished form–I want you to just watch and see if I’m not right in what I say: that the white man, in his press, is going to identify me with ‘hate.’”

Today, we associate Malcolm X with advocacy and evolution. He was a legacy cannabis dealer decades before the plant became legal, making him an unsung symbol of the War on Drugs, and the continuing struggle for equity and equality in America.