For tens of thousands of years, many cultures all over the globe have used psychedelics. These natural substances were often used in sacred or religious ceremonies to help see the divine or commune with God, or for relief of certain ailments.

LSD and other psychedelics were widely researched in the 1950s and ‘60s to treat numerous maladies, but in the US, research was largely stopped with the passing of the Controlled Substances Act in 1970.

Today, there has been a resurgence in psychedelics, with an emphasis on their use for treating issues such as substance dependency, PTSD, depression, and anxiety, and to help with end-of-life care.

Ancient cultures

Some ancient Greeks supposedly consumed a psychedelic substance. The cults of Demeter and Persephone performed an initiation ceremony every year called the “Eleusinian Mysteries,” during which they would consume a drink called “kykeon,” thought to contain psychedelic properties. Theories suggest the substance was derived from Ergot fungus, of which LSD is also derived.

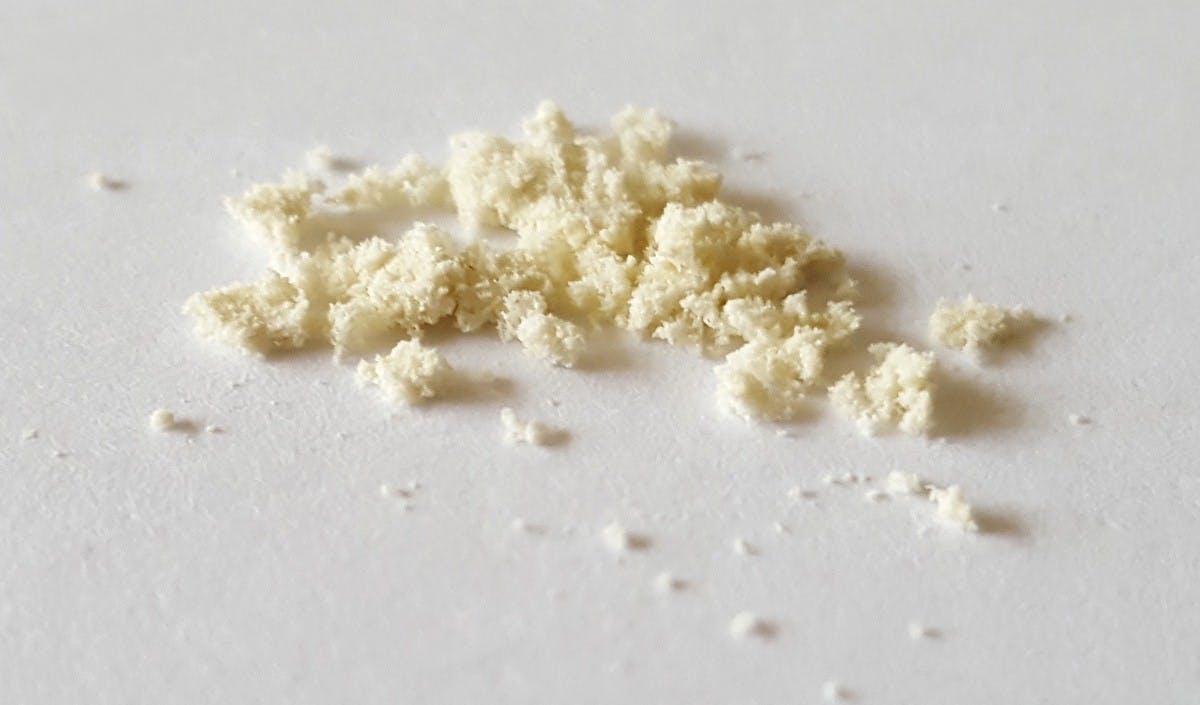

Ancient Sanskrit text refers to “soma,” a plant juice that was consumed during Vedic sacrifice ceremonies in ancient India as an offering to the gods. Known for its hallucinogenic properties, soma is speculated to have come from Amanita muscaria or Psilocybe cubensis, types of psychedelic mushrooms, or a type of climbing plant called Asclepias acida.

Mesoamerican cultures such as the Aztecs, Mayans, and Incas were known for consuming psychedelics such as peyote, mescaline, psilocybin mushrooms, and others. In Aztec culture, mushrooms were referred to as “Teonanácatl,” meaning “flesh of the gods,” and taking psychedelics was a means of altering consciousness, communicating with the gods, and becoming one with nature.

Ayahuasca, a brew derived from the mixture of a woody vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) and the leaves of the chacruna plant (Psychotria viridis), was consumed for spiritual and medicinal purposes by tribes in the Amazon going back 1,000 years or more.

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries nearAncient Mesoamerican and South American cultures emphasize the role of the shaman, who oversees the psychedelic experience. A shaman’s purpose is to help guide an individual consuming psychedelic substances into the spirit world and through altered states of consciousness. The psychedelic experience can be overwhelming and frightening and usually involves vomiting and diarrhea.

Psychedelics in the 20th century

In 1938, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann accidentally discovered LSD. He was experimenting with the fungus ergot, which grows in rye kernels, while working in a lab at pharmaceutical company Sandoz, when he isolated the chemical lysergic acid diethylamide—LSD.

The substance was ineffective for the project he was working on, so Hofmann put it aside. But something about the substance intrigued him, and five years later he revisited it. When synthesizing the substance again, he absorbed trace amounts of it and noticed its powerful hallucinogenic effects.

On April 19, 1943, Hofmann intentionally ingested a higher dose of LSD. The event became known as “Bicycle Day,” as Hofmann started to feel the effects of the LSD as he rode his bike home, and it was the first intentional acid trip in history.

He experienced visual distortions, dizziness, almost fainted, and saw what he described as “demonic transformations.” A doctor was called, but by the time he arrived, Hofmann had lapsed into a “feeling of good fortune and gratitude,” and was enjoying kaleidoscopic images when he closed his eyes, he would later say. In the morning, he reported that a “sensation of well-being and renewed life flowed through me.”

Hofmann would go on to become a life-long advocate of the drug, extolling its therapeutic benefits and abilities to open up consciousness and make individuals more aware.

Psychedelics in psychiatry

In the early 1950s, psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond and Abram Hoffer pioneered the use of LSD to treat alcoholism while working in a clinic in Saskatchewan, Canada. Osmond would later coin the term for these new types of drugs “psychedelics,” meaning “mind-manifesting,” after supervising writer Aldous Huxley on a mescaline trip. Huxley would later immortalize the experience in his book, The Doors of Perception.

Osmond and Hoffer’s biochemical approach initially treated two subjects for alcoholism with LSD—one quit drinking right away and the other quit within six months after treatment. Osmond and Hoffer expanded the study to more than 700 patients over the next 10 years and claimed similar results.

Meanwhile, in the UK, Ronald Sandison was also using LSD in conjunction with psychotherapy to treat patients with neurosis and other ailments with great success. In one study, Sandison reported that 60% of patients recovered or improved with treatment of LSD and psychotherapy when those patients hadn’t responded to conventional therapy.

LSD was researched throughout the 1950s and ‘60s to treat various conditions, including depression, schizophrenia, autism, and terminal cancer, among other ailments. Research on LSD was conducted over 1,000 studies involving 40,000 patients, with minimal adverse incidents.

The ’60s

In 1962, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) passed the Drug Amendments of 1962, which introduced new restrictions on clinical trials and drug testing, in turn restricting the use of LSD and other psychedelics for therapeutic use.

Around the same time, hippie counterculture in the US latched onto LSD and other psychedelics. Altering one’s mind, expanding consciousness, connecting with one another, and the desire to “Turn on, tune in, and drop out,” in the words of Timothy Leary, gave LSD and other psychedelics a bad name.

With LSD in particular, illicit manufacturing proliferated, and the general public started to view it and other psychedelics as street drugs. LSD manufacturer and patent-holder Sandoz lost interest in continuing to produce the drug and tried to distance itself from it.

As hippie counterculture protested the Vietnam War and called for civil, racial, and gender rights, it faced a backlash from the political establishment of the time, as well as anything and everything associated with the counterculture movement, including psychedelics.

Prohibition and the War on Drugs

In 1970, Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act, classifying LSD and other psychedelics, such as psilocybin, DMT, and mescaline—as well as cannabis—as Schedule I drugs, the most restrictive level.

After the passing of the Act, for example, possession of one to nine grams of LSD as a first offense will get you one year in prison, a $1,000 fine, or both. However, possession of more than nine grams of LSD can be treated as possession with intent to distribute, for which the penalty is five to 40 years, a fine of up to $2 million, or both.

Research on LSD and psychedelics in general all but ground to a halt.

Psychedelics today

Today, attitudes toward the War on Drugs are changing as people realize how disproportionately it affects Black and Latino Americans, and acknowledge the incredible amount of money wasted on it. Attitudes on how psychedelics and cannabis can offer incredible medical and therapeutic benefits are also changing.

In 2019 and 2020 alone, the psychedelics movement gained steam. Piggybacking on the cannabis legalization movement, several cities, states, and districts have decriminalized psychedelics or entheogenic plants:

- Denver, Colorado in May 2019

- Oakland, California in June 2019

- Santa Cruz, California February 2020

- Ann Arbor, Michigan in September 2020

- Washington, DC in November 2020

Additionally, the state of Oregon legalized the medical use of psilocybin under the care of a licensed facilitator in November 2020.

By providing us with your email address, you agree to Leafly's Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.