In line with modern prohibition and restrictive drug legislation, the Great White North’s original drug laws were rooted in bigotry and disproportionately affected Indigenous, Black, Asian, Latinx and vulnerable communities.

Canada’s first foray into prohibition was largely driven by the anti-Chinese racism that had become rampant in British Columbia during the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway, when an influx of Chinese immigrants settled in and around Vancouver.

The Opium and Drug Act of 1908 rendered it illegal for Canadians to sell, manufacture, or import opiates and cocaine for non-medical use. The law targeted Chinese Canadians, who bore the brunt of the arrests and ensuing legal penalties.

The ensuing moral panic over illegal drug use spread east across the country, and alarmist, early “war on drugs”-type media began to proliferate, creating the foundations of a social stigma around drug users.

Tomes such as The Black Candle, penned by suffragist and first female magistrate Emily Murphy,perfectlyencapsulate the Canadian public’s perception of race and drug use at the time.

Notably, it also categorically defined addiction as a legal issue as opposed to a public health concern. With the 1922 publication of the book, Murphy aimed to inspire the public to demand the implementation of stricter drug laws. Her hopes would soon come to fruition.

The1908 Act laid the groundwork for future legislation prohibiting other drugs, with cannabis becoming a scheduled substance in 1923 when drug legislation was consolidated into the Act to Prohibit the Improper Use of Opium and other Drugs. There is no evidence that the Act was ever discussed or debated in Parliament.

The Opium and Narcotic Act followed in 1929, establishing strict penalties for those caught consuming, possessing or selling illegal substances. The legislation would be the foundation of Canada’s drug policy for the next 40 years.

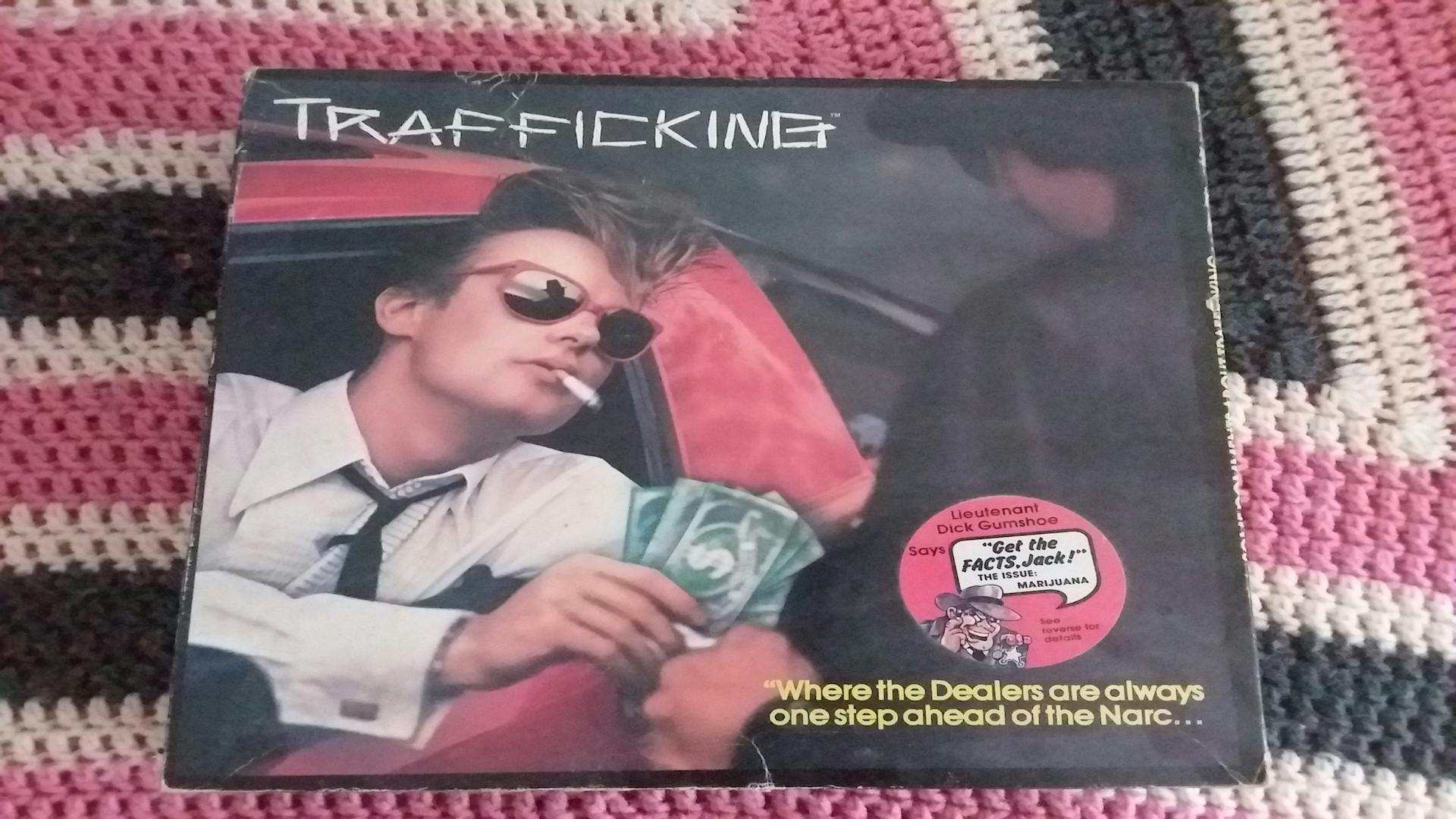

At the dawn of the psychedelic 60s, recreational drug use became an increasingly influential part of youth culture. Enter the 1961 Narcotic Control Act, which rendered the possession of cannabis (and various other drugs) an indictable offence and doubled the penalty for trafficking from seven to 14 years.

The Act also implemented elements of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, an international treatyof which Canada was a signatory and which would later be supplemented with further legislation controlling activities related to psychotropic substances such as MDMA and LSD.

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries nearBut amid the arrests of Canadians with otherwise clean records, the government launched the Le Dain Commission to examine the use of non-medical drugs. The Commission advocated for more lenient drug penalties, but the prohibition remained intact and unchanged.

In 1996, the Narcotic Control Act was repealed and replaced with the Controlled Drug and Substances Act, decreasing the penalties for possession of cannabis. The Act remains in place today, albeit with multiple amendments.

Indigenous cannabis remains in federal vs provincial law limbo

The Cannabis Act ostensibly legalized weed for all residents of Canada but left gaping holes with regard to the acknowledgment of Indigenous sovereignty.

Many groups were dismayed at the lack of consultation in the development stage, and further frustrated to see that the legislation made no provisions to protect Indigenous sovereign, inherent, and treaty rights as they relate to cannabis.

The National Indigenous Medical Cannabis Association (NIMCA) issued a scathing criticism of Bill C-45, accusing the government of developing the legal framework without consideration for the unique situation of Indigenous people.

“Once again, Canada is proving it is not onside with First Nation and Indigenous peoples and our sovereign and Inherent rights. The current Liberal government promised to respect our Inherent, treaty and land rights and to honour us with a nation-to-nation relationship,” reads the statement.

“None of the promises have been kept and most of all, there has been a complete lack of consultation with Indigenous peoples on many issues including cannabis and the development of the proposed Bill C-45. This does not demonstrate respect for our sovereign rights or to be true partners in this confederation.”

Raids on unlicensed dispensaries have taken place on Indigenous treaty and unceded lands in multiple provinces since legalization came into effect.

Terry Parker and the first medical cannabis exception

The first blow to Canada’s cannabis prohibition was dealt in 2000 as a result of R. v. Parker, a monumental case viewed by many as the first step towards federal legalization.

The catalyst was the 1996 arrest of medical consumer Terry Parker, who suffered from epilepsy and found cannabis to be an effective treatment for his seizures. Opting to grow his own plants, Parker was arrested after a police raid on his home and charged with cultivating and possessing cannabis under the now-defunct Narcotics Control Act.

Parker abjectly refused to stop growing and sharing his crop with other patients, which resulted in further charges against him after a second police raid on his home a year later yielded more plants. Parker asserted in court that consuming cannabis was a necessary element in the control and treatment of his illness. The charges were stayed, and Parker was granted an exemption from the law.

The Crown appealed, but the Ontario Court of Appeal sided with Parker.

“Liberty includes the right to make decisions of fundamental personal importance, including the choice of medication to alleviate the effects of an illness with life-threatening consequences,” reads the landmark decision.

“Deprivation by means of a criminal sanction of access to medication reasonably required for the treatment of a medical condition that threatens life or health also constitutes a deprivation of security of the person.”

The case triggered the federal government to draft the Marihuana Medical Access Regulations in 2001, which granted patients who met certain criteria a legal exemption that allowed them to consume and possess cannabis. It would take another seventeen years for adult-use cannabis legislation to come into force.

Much like the United States, cannabis prohibition in Canada has racist roots

Canada’s history of prohibition is firmly grounded in racist ideology, and the justice system’s unequal treatment of people of colour persists in the present day. Arrests for cannabis-related convictions have disproportionately affected Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latinx folks, although there are few resources that collect race-based crime data in Canada.

A 2020 study from the Ontario Human Rights Commission found that in pre-legalization Toronto, Black people represented 34.4% of those involved in single-charge cannabis possession cases, despite representing only 8.8% of the population. This indicates that Black people were 3.9 times more likely to be involved in a single-charge cannabis possession case, whereas other racial minority groups were under-represented.

A 2021 analysis of five major Canadian cities published in the International Journal of Drug Policy found that “with just one exception… both Black and Indigenous people are over-represented amongst those arrested for cannabis possession across the five cities examined.”

Another analysis from the same University of Toronto found that this trend appears across the Canadian justice system. The authors found that approximately twice as many Black youth are stopped by police compared to their white peers, and Black people were 50% more likely to be taken to a police station for processing post-arrest, “even taking into account criminal history and age.” In federal prisons, Black people are over-represented by “more than 300% vs their population,” whereas Indigenous people were over-represented by nearly 500%.

While these data are relatively recent, the trends are not. Decades-old findings from documents such as the 1995 Report of the Commission on Systemic Racism in the Ontario Criminal Justice System and the 1991 Report on the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba revealed similar patterns in the treatment of BIPOC within the Canadian justice system.

Weed won but the work isn’t done: Mitigating the damage of prohibition

The end of cannabis prohibition did not signify the end of pot persecution for many Canadians.

Before October 2018, an estimated 500,000 Canadians were convicted of simple cannabis possession. In 2017, the year before cannabis became legal, over half of all police-reported Controlled Drugs and Substances Act offences were cannabis-related, according to the Department of Justice. Seventy-four percent of those charges were for possession.

The Canadian government implemented a Cannabis Record Suspension program, the initiative was widely criticized as being narrow-reaching and complicated. Instead of issuing a blanket pardon, those seeking a suspension must submit an application to the Parole Board of Canada. Only those charged with simple possession are eligible to apply.

The government estimated that 10,000 Canadians would be eligible for a record suspension. As of October 2021, the Parole Board of Canada reported that only 484 applications had been received since the program’s launch in 2019.

While the damage caused by prohibition can never be undone, advocacy groups like NORML Canada, Medical Cannabis of Canada, and Cannabis Amnesty are making moves to mitigate the damage wrought by the thousands of criminal convictions for non-violent cannabis offences across the country.

Advocacy groups are also pushing for legislative changes such as the removal of the cannabis excise tax for medical consumers, the legalization of consumption lounges, and the right to grow cannabis at home in every province.

Did the Cannabis Act legalize weed for everyone?

While cannabis prohibition may be a thing of the past in Canada, many consumers still face significant barriers to legally accessing and consuming weed.

Provincial regulations that allow landlords to ban or restrict consumption via smoking or vaping are the norm, meaning only those who own their residences (i.e. wealthier consumers) are guaranteed the right to consume cannabis at home in the manner of their choosing.

Most provinces ban or heavily restrict smoking and vaping in public places, which often include sidewalks, streets, and local parks. As a result, people experiencing homelessness, renters, and frequent medical consumers (especially those with limited mobility) are effectively banned, or at least seriously constrained, from legally consuming the drug without risk of penalty.

Even buying cannabis from a licensed retailer can come with complications. Unlike in stores that sell alcohol, where minors are permitted to enter with their parents while they shop, cannabis dispensaries only allow those of legal age to enter the store, complicating the efforts of solo parents to purchase their weed products from the legal market.

Growing cannabis at home can reduce the cost and render cannabis more affordable, but at the time of publication residents of Quebec and Manitoba are currently unable to legally grow the four plants at home to which residents in other provinces are entitled.

The ongoing legal battle over home growing in Quebec was heard by the Supreme Court in September 2022, and the public is currently awaiting a decision. But even if the justices rule in favour of allowing home cultivation, those who rent their homes may still be restricted from growing their own, as provincial legislation allows landlords (and some condo associations) to ban cannabis cultivation in rental units.

Advocacy is just as important now as it was pre-legalization

As we celebrate four years of legalization it is important to keep in mind that nearly one hundred years of prohibition cannot be undone easily or quickly. Systematic barriers are just that, systematic. Until November 21, 2022, Health Canada is asking for consumer engagement from anyone who has something to say about legalization. They are also inquiring about improvements that could be made to the Cannabis Act. For those who wish to have a voice in areas like consumption lounges, medical access, pardons, and creating an equitable industry, check out the survey here.